Training Your Hunting Dog From an Amateur’s Perspective

When I developed the “Hunting With Hank” television series starring my Llewellin Setter Hank, for what was then The Outdoor Life Network, I had confidence that the series would find an audience. But, the amazing success of Hank’s show actually caught me off guard. Along with its popularity, came requests from viewers all across the country to explain how I trained Hank for the work they saw him performing on our upland bird hunts that spanned the country.

As a consequence, I developed my seminar, “Training from an Amateur’s Perspective.” At countless sportsmen’s shows, Hank and I put on these seminars to large audiences made up of Hank’s fans and bird-dog owners. At those seminars I demonstrated how I trained Hank using a technique called “Successive Approximation.” When I retired Hank and began the follow-up series “Dash in the Uplands” with his son Dash, I continued those seminars for Dash’s fans as well.

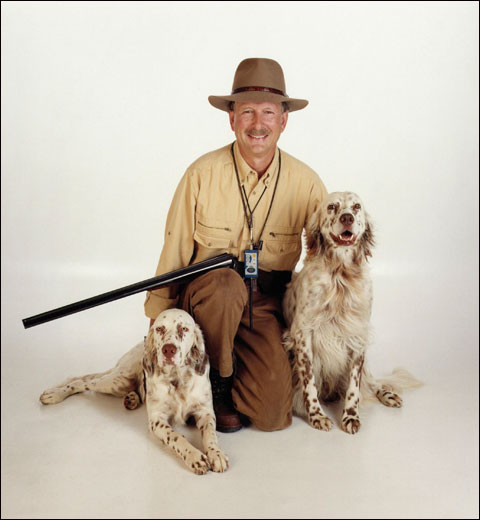

Dash, Hank and Dez.

Dash, Hank and Dez.

As I did at the beginning of each seminar, let me state here that I’m NOT a professional trainer, I’m just a bird hunter, so I can only share with you what I did to get my “boys” ready for their bird-hunting adventures on camera. In so doing, I hope there might be something in my approach that will be helpful to those of you who are also amateur dog trainers trying to mold your dog into a fine, four-legged hunting partner.

Let me first define “Successive Approximation.” It’s a behavioral term that refers to: gradually molding or training an organism to perform a specific response by reinforcing any responses that come close to the desired response. Now, in your mind, substitute the word organism with the term bird dog.

OK, let’s get started. When I first got Hank I was terrified to try to train a pointing dog. I had trained Labradors for duck hunting, but Hank was the first pointing dog I ever owned. Before he arrived at our home at the age of seven weeks, I read everything I could get my hands on about training pointing breeds. Like most people, I agreed with some authors and disagreed with others. I finally settled on the method that eventually helped Hank and Dash become inducted into the National Bird Dog Museum as the only two television birddogs so honored.

Dash already pointing.

Dash already pointing.You’ve seen the formal definition of “Successive Approximation,” so now let me give you my interpretation of it. With each training segment there is an end result that the trainer is seeking. It can be as fundamental as “heel,” to as complicated as retrieving a bird to your hand. All along the way, each training goal needs to be clearly defined in your mind before you begin the sequence that will accomplish that goal. For instance, let’s say that the training goal is to have your dog “heel” at your side without a leash. That is the end result. To get there you use “Successive Approximation” steps.

Here’s how I did it with Hank and Dash when I started their training at the age of seven weeks. A light-weight collar and leash were used (they were just little guys). As a left handed shooter, I wanted my boys to heel on the right side so I attached the leash and stood on the left to begin this training. Remember, just because you use a word like “heel” the dog has no concept of what it means the first time it hears that sound. The command has to be demonstrated. So with Hank at my side, and the leash attached to the collar, here’s what I did. I tightened the slack on the leash, used his name followed by the command… “Hank, HEEL”. I began walking forward. Hank at first tugged back and tried to break free (I don’t blame him). I repeated the command, “Hank, HEEL” over and over again. When he gave up and started walking beside me, I immediately stopped, knelt down and praised and petted him.

Dez and Hank.

Dez and Hank.After a few moments, I repeated the exercise. “Hank, HEEL”. Each time, I tugged on the leash as I gave the verbal command. Now here’s how “Successive Approximation” works. Remember, the end result was to have him heel without a leash. Once I felt Hank understood the command, I loosened the tension on the leash. “Hank, HEEL”. This time he came along beside me without needing to tug him along. He was making progress toward the goal of walking beside me without the leash.

With a few more training sessions, Hank would walk beside me without any tugging on the leash once he heard the command. Next, to see if he was ready to heel without the leash, I removed it, gave him the command, and he began walking next to me. If he faltered, I would simply put him back on the leash to reinforce the command. After several sessions, Hank learned to walk beside me on the right side…mission accomplished.

Dez and Dash in Nevada.

Dez and Dash in Nevada.Next, I wanted to teach him to “whoa.” This command is not only an important control command, it could save your dogs life sometime by stopping it before it crosses a busy street, or any number of situations where it could get into serious trouble. Of course, this is also a command used to help a dog hold its point when it has bird scent in its nostrils. The end result of teaching this command is to have your dog stop any time you say. Here’s how I got Hank and Dash to do that. Let’s use Hank again as the example.

With him on the leash, and at my right side, I gave the command, “Hank, HEEL.” After walking several feet that way, I tightened the tension on the leash, pulled back on it and gave the command, “Hank, WHOA.” I then stood still for several seconds, having

released the tension on the leash. After several moments, I again tightened the tension on the leash, gave the command, “Hank, HEEL,” and walked forward. Several moments later, I tightened the tension on the leash, gave the command “Hank, WHOA” and stopped.

Dez and Dash taking a break in Montana.

Dez and Dash taking a break in Montana.This sequence was repeated over and over again. To see of he understood the command, I then gave the whoa command WITHOUT tugging on the leash. When he stopped, I knew he understood. To complete this training segment, the final test in the successive approximation method was to give the command while he was off the leash. We walked forward together, with Hank at heel. I gave the command “Hank, WHOA” and he stopped!

Those are just two examples of how the successive approximation method worked for me as I trained first Hank and then 10 years later, his son Dash. Each of the boys had to learn several more commands of course, but each training step was designed to reach a certain goal.

Of all the things I wanted from Hank and Dash, the most difficult training for them and for me was teaching them to retrieve to hand. Growing up hunting pheasants in Eastern Oregon, I learned early that if a pheasant wasn’t hit hard, it would run as soon as it touched ground. And if a bird dog couldn’t bring a pheasant to hand, it would start a hectic scene of chasing an escaping bird that often times eluded both dog and hunter.

So, the end result was to have every bird brought to my hand before it was released by Hank or Dash. To accomplish that, I put them (and me) through the toughest part of their training. Again, I’ll use Hank as an example since he was my first pointing dog. I began by securing Hank to an overhead beam, with his leash. Placing my hand over his muzzle, I squeezed gently on his upper teeth and gums, and said “Hank, FETCH.” I quickly inserted a small wooden dowel into his mouth and held it there with an additional command “HOLD.” He really didn’t like that at all. He fought to get the dowel out of his mouth, but I held firm.

Dez and Dash wingshooting in Vermont.

Dez and Dash wingshooting in Vermont.After a few moments, I released the pressure, and removed the dowel, praising Hank as I did. Then I repeated the exercise over and over again until he would open his mouth voluntarily on command. The, I held the dowel a few inches from his mouth and repeated the command. He reached out to take it. Then, I placed it on the garage floor and repeated the command. He stretched out and picked it up. Then, I took him off the leash, tossed the dowel to the end of the garage and repeated the command. He went to it and picked it up and brought it to me. Then, I took Hank outside, and tossed the dowel into the backyard. He got it and brought it back. I then took him to a park and tossed it as far as I could. He got it and brought it back. I introduced a retrieving dummy with a pheasant wing attached. He loved that part of the training, and that command was done.

It wasn’t easy for either of us, but the end result was that Hank loved retrieving birds, and brought every bird to hand with great enthusiasm for the rest of his hunting life. It was Successive Approximation that accomplished that goal as well as all of the other lessons I taught Hank and Dash.

“Successive Approximation” worked on all aspects of my training efforts. From basic social commands like: heel, whoa, down and stay to field commands of quartering, pointing, backing or any other necessary commands to make your hunting companion work as a team member with you.

Oh, there’s one more lesson, but this one is for you. As I said in each of the 135 episodes of our Hank and Dash shows (with my tongue firmly planted in my cheek), never, EVER spoil your birddog!

Dez Young had spent 30 years in broadcast before developing the Hunting With Hank TV show in 1995. The series started airing in 1997 on the Outdoor Life Network. His subsequent TV shows include Dash in the Uplands, Upland Days With Dash and Dez, and Dez Young’s Wingshooter’s Journal.

Useful resources:

Dez Young’s HWH Productions web site

Dez Young had spent 30 years in broadcast before developing the Hunting With Hank TV show in 1995. The series started airing in 1997 on the Outdoor Life Network. His subsequent TV shows include Dash in the Uplands, Upland Days With Dash and Dez, and Dez Young’s Wingshooter’s Journal.

Comments