Heeding the Call of an Eastern Shore Goose Hunt

There’s a state of mind that numbs you to hunting adventures, even though the drive is only two hours east. Planted in front of a computer for another 12-hour marathon, collapsing after dinner on the sofa in big-screen semi-consciousness watching fighters with shaved heads tattooed to the max sporting nick-names like “The Refrigerator,” “Meat Missile” and “Freak Show” square off in the MMA octagon to kick, elbow and pummel their opponent’s faces into bloody goo, it’s sublimely painless to slip into a rut barren of outdoor aspirations.

In retrospect, the wingshooting gods had conspired to present a goose hunt on my home turf of the fabled Maryland Eastern Shore that would impose a much-needed break from work.

Fate works in mysterious ways. A business trip to Orvis’ Sandanona Shooting Grounds in Millbrook, New York landed me within striking distance of Andover, New Jersey, where Griffin & Howe’s Hudson Farm was hosting its Annual Showcase & Sporting Clays Invitational to benefit Wounded Warriors in Action. The two-day event included shotgun and rifle trials, a sporting-clays competition and exhibitors such as Krieghoff International, Highland Hills Ranch, Remington Custom, Luciano Bosis, Holland & Holland, Good Shot Design, James Purdey & Sons and Belvoir Castle-Her Grace The Duchess of Rutland.

Matt Disotell with two of the geese taken on our hunt.

Matt Disotell with two of the geese taken on our hunt.

In the luxurious white tent on that warm, autumn afternoon, I met Matt Disotell, owner of Eastern Shore Guide Service in Elkton, Maryland. A life-long hunter originally from Northwest Louisiana, Matt had been guiding waterfowl for 20 years throughout the U.S., but most recently in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic. For the past three years, Matt has operated as a Remington Pro-Staffer — shooting their guns and ammo and appearing at events like Griffin & Howe’s Annual Showcase & Sporting Clays Invitational under the banner of Remington Custom.

As we talked about an Eastern Shore waterfowl hunt, it gradually became apparent the historical flats and marshes acknowledged as a national treasure for waterfowlers had been ignored far too long as I spent most waking hours immersed in work. Matt suggested we meet in Chestertown, Maryland – a 300-year-old fishing town on the Chesapeake Bay 90 miles from home. I wondered: What took so long?

Decoys on the stern of the Jo-B-Mar II.

Decoys on the stern of the Jo-B-Mar II.

The last time I hunted on the Eastern Shore had been 2½ years before — sea ducks on the Kent Narrows with Captain Tom Quimby aboard the 40-foot Jo-B-Mar II. There was an exquisite quality to the morning as we motored through the bone-still surface ice. A blush pink daybreak materialized over tiny Parsons Island. Expansive formations of blue-bill ducks passed high in the lavender haze. We glided through a soft dream. About an hour out, Captain Tom spread a string of long-tail decoys – their black and white bodies a nautical necklace around the 30-year-old boat. Search for the meaning of “blessing” and that morning on the Eastern Shore would clearly qualify.

For many waterfowl hunters, goose and duck expeditions on the Eastern Shore carry the cache of walk-up pheasants in North Dakota or high-volume doves in Argentina.

Matt Disotell’s decoy spread in the still Eastern Shore morning minutes before we could begin to legally hunt.

Matt Disotell’s decoy spread in the still Eastern Shore morning minutes before we could begin to legally hunt.

The Eastern Shore, though, has been commercializing waterfowl hunts for some 250 years. Ducks and geese intermixed with blue crabs, oysters and fish comprised the daily bounty sent to markets as far north as New York City via trains that left from Baltimore and Havre de Grace ever since the rails had been laid. In the mid-19th century, multi-barrel, semi-autos and even massive punt guns stuffed with a pound of shot and nails decimated waterfowl populations to feed the new wave of European immigrants and the nouveau riche that gave rise to enormous urban markets for the birds.

The mid-1800s saw a rush of innovation in waterfowling on the Eastern Shore. Havre de Grace, Maryland turned into a decoy boomtown with perhaps the highest concentration of carvers in the world. Local hotels had bundled waterfowl hunting packages. When a pair of Newfoundland dogs was rescued from a shipwreck in 1807, they were bred with water spaniels to create the legendary Chesapeake Bay Retriever.

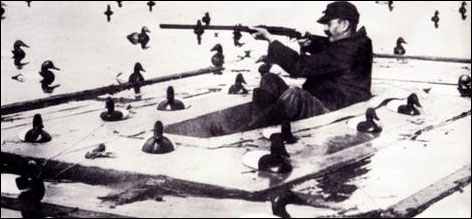

A sink box from the early days of waterfowl hunting on the Eastern Shore.

A sink box from the early days of waterfowl hunting on the Eastern Shore.

At night, emboldened hunters in a low scull boats infiltrated flocks and opened fire. Sink boxes festooned with hundreds of decoys set the stage for slaughter. Perhaps no Eastern Shore hunter was more prolific than Atley Lankford who reportedly killed more than 500,000 ducks during his lifetime dating from the early 1900s.

The federal government attempted to stem the carnage. The Lacy Act, enacted in 1900, and the Federal Migratory Bird Act of 1918, aimed to control or ban market hunting as well as regulate sport hunting. The eelgrass blight of the 1920s, compounded by the Great Depression, accelerated the decline of Eastern Shore waterfowl. Despite Federal prohibitions in 1937 of live decoys, sink-box blinds and a three-shell limit in semi-automatic shotguns, an outlaw community of Eastern Shore waterfowlers reportedly used punt guns into the 1950s.

Between the 1960s and mid-1990s the hunting persevered during the 90-day season that stipulated a daily bag limit of three Canada Geese. A combination of over-hunting, poor legislation, climate change and real-estate development caused the Canada Goose population to thin during those 30 years. Daily limits continued to shrink until 1995 when the migratory goose season closed entirely to replenish the Atlantic flock. The moratorium lasted for seven seasons. Come 2001, the Canada Goose population exploded — recalling the heydays of Eastern Shore goose hunting.

I had grown deaf to the raucous history of Eastern Shore waterfowling that murmured in the wind — supplanted by the tap, tap, tap of the computer keyboard and ringing telephones. That conversation with Matt at Hudson Farm was a heads-up to rediscover the neighboring marshes and flats with a revitalizing goose hunt.

Rick Cundiff shooting at incoming geese.

Rick Cundiff shooting at incoming geese.

When I mentioned it to my friend, Rick Cundiff, he immediately jumped on-board. As the COO of investment banking firm, Townsend Capital in Hunt Valley, Maryland, Rick had logged hundreds of hours during the year flying to Europe, Asia and the Midwest on business at the expense of any bird hunting. As proof, a new Benelli Super Black Eagle II he bought a year ago for a Saskatchewan duck hunt remained boxed and unfired after cancelling that trip. Now Rick would shoot his Benelli for the first time. Gun-wise, I felt equally pitiable. A new Ithaca Model 37 Waterfowl 12 gauge stood in my safe completely ignored…never shot.

Up at 3:00 am., Rick and I drove two hours to meet Matt at the McDonald’s in Chestertown — a community of about 5,000 people established in the early 1700s on the banks of the Chester River. A mid-18th century shipping boom had fostered a thriving merchant class. Today, Chestertown is an artsy tourist destination with a waterfront promenade.

Brian Long, in the blind, inspecting a goose that was just shot.

Inside the bright restaurant, the hunt’s karmic vibes reached full circle. With Sandanona Shooting Grounds as the springboard to Hudson Farm where I met Matt, there at the Chestertown McDonald’s he introduced Brian Long, who with his wife, Peggy, manages the Sandanona Shooting Grounds.

After wolfing down an Egg McMuffin and hot coffee, we drove through the darkness along county roads to a trail that ultimately revealed a waterfront farm occupied by a ramshackle house. Our flashlights pierced the marshy landscape as we geared up and walked a path toward the silhouette of a grassy blind. Without dogs, our footfalls remained the solitary sounds as first light appeared on the horizon.

Matt Disotell gathers decoys after the hunt that were stowed in his blind.

Matt Disotell gathers decoys after the hunt that were stowed in his blind. We handed the V-board and body decoys over the bushy façade to Matt who, in waders, laid out a modest spread in a shallow estuary about 40 yards wide dammed near the blind. The indigo sky progressively infused with the pastels of sunrise. During the thirty-minute countdown until we could legally hunt, our conversation turned to Italian food.

Canada Geese broadcast their arrival of the small formations clearly out of range. But Matt’s remarkable calls brought them around within sight of the decoys and on his command we opened fire on the descending geese that glided down in our volley soon to be dispatched in a morning otherwise serene.

Within five passes of Canada and Lesser Geese, we reached our limit several hours later of two per hunter. As we stowed the decoys, the vast expanse of water and grasses conjured the continuum of Eastern Shore waterfowling that thankfully touched my soul.

Irwin Greenstein is the Publisher of Shotgun Life. You can reach him at letters@shotgunlife.com.

Helpful resources:

The web site for Matt Disotell’s Eastern Shore Guide Service

The Hudson Farm web site

The Orvis Sandanona Shooting Grounds web site

Irwin Greenstein is Publisher of Shotgun Life. Please send your comments to letters@shotgunlife.com.

Comments