A Call for Conservation – The Upland Stamp

When we think of bird hunting, we instantly go to a sacred place that exists in our hearts – a sacred covert we protect. We dream of finding that place again and want to know it will still be there long after we are gone. As a group, we engage in friendly debates about the dogs, guns and game we prefer. We share our stories, but it’s that moment we find alone in the field that we think about at the end of the day, in a comfortable chair. The birds we hunt are worth finding for the first time, worth fighting for and worth remembering.

American landscapes are forever changing as we face the loss of some of our most iconic game bird species. Grassland birds are among the fastest and most consistently declining bird populations in North America, and grassland and prairie habitats are the fastest disappearing habitats in the US. Last year, the Gunnison sage grouse and Lesser Prairie-chicken were listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. The Greater Sage Grouse, Greater Prairie-chicken, Sooty Grouse, and Northern Bobwhite have experienced a 40% rate of decline in the last 40 years. Scaled Quail and Sharp-tailed Grouse are also showing steep declines.

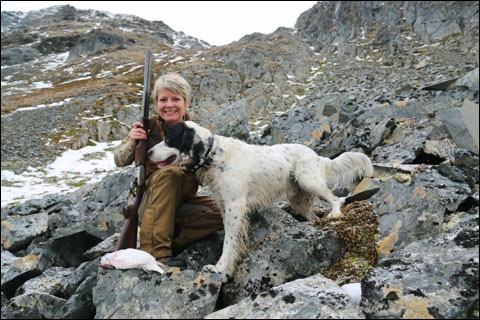

Christine Cunningham on a hunt for white tailed ptarmigan in Alaska’s Kenai Mountains with her English setter, Winchester.

Most of us who spend our time outdoors agree that something is going wrong for game bird species. It isn’t the first time in history we’ve faced the prospect of losing abundant game. In the early part of the 19th century, sportsmen united in a wildlife conservation effort. We created many of the sportsmen’s clubs and conservation groups that still exist today. We led a cultural conservation ethic and within a few generations, we could sit back in our chairs again and know that we had restored wildlife. Today we pay for licenses, stamps and memberships. Even if our own coverts are safe for now, we can’t ignore the national conservation crisis for upland birds.

On March 5, 2015, Ultimate Upland introduced a petition for the Federal Upland Stamp for upland habitat conservation in the article, It’s Time for a Federal Upland Stamp. As a group, we responded with a wide array of support and dissent. Some of us said we do not want to pay “another cent” to conserve the habitat required to sustain upland birds. Some of us said we would only pay if there are guarantees on how the funds are spent. On the opposite end of the spectrum, some of us said we would pay such a high price that it may exclude the average hunter. Although the idea came as news, it’s one that has been batted around for years. Now is the time.

One of the things we talk about as bird hunters is how we can love the birds and shoot them. There’s an internal disconnect, and the responsibility we take as conservationists and activists provides the balance. Historically, it has been those of us who hunt and shoot who have supported the cost of wildlife management. The existence of a healthy population of upland birds represents the American countryside at its best. Unlike waterfowl, which migrate and are easily seen in the sky and on the water, upland birds are called “backyard birds” or “resident birds” because they are often nesting in our neighboring woods and fields. They are elusive and camouflaged to their varied environments, hiding invisibly in fence lines, coverts, plum thickets and sagebrush.

Prototype of the Upland Stamp Group developed by artist Shari Erickson (courtesy of Ultimate Upland).

As a hunter, my relationship with the birds I hunt means I must take a personal responsibility when their numbers are in decline. This conservation ethic is part of how we make ourselves worthy of the game. Upland hunters have a unique understanding of why upland conservation must come first. We have an opportunity to save our upland bird heritage and make upland conservation a priority, much like waterfowl hunters have with the purchase of stamps for decades.

If it were not for the duck stamp, it’s quite possible certain waterfowl species would never have recovered. It’s a program that has raised over $800 million for conservation and added 6 million acres to the National Wildlife Refuge System. It is a living example of stewardship and demonstrates the responsibility hunters take for the birds we pursue. The stamp has provided a pattern of inclusiveness that allows for a healthy relationship between sportsmen and the wildlife viewing public. It’s a pattern for success that bird hunters and bird enthusiasts can replicate for upland species. The benefits of an upland stamp to conservationists, collectors, and artists includes an educational aspect and opportunity to highlight the cultural value of upland game species to broader audiences.

There are several reasons an Upland Stamp cannot follow the Duck Stamp model even though it replicates its pattern for success. The Wildlife Restoration program (Pittman-Robertson) serves as perhaps a better management framework. If the Upland Stamp followed this model, it acts as a long-term source of dedicated funding for the conservation of upland habitat that not only preserves State management authority but encourages states to undertake projects benefiting upland game species. Protections against the use of funds for any other purpose, including opposition to the taking of game result in the same penalties as included in the Pittman-Robertson Act. The matching component and period in which funds must be utilized incentivizes states to use the funding to prioritize upland bird projects.

That our government can be difficult, inefficient, or out of touch with the people is without question. It is up to us to keep current with efforts to save the birds we love, support grassroots conservation, contact our representatives and commissions, and reach out to the land managers in our areas to find out if there’s something we can do. There isn’t a group with more passion for the whole of what we do than bird hunters. In order for a dedicated funding source to exist for upland birds, we have to come together as a group in support of an idea that will work.

For more about the upland stamp or to sign the petition, visit www.uplandstamp.org.

Attached is the article for the upland stamp we talked about earlier this week. I’ve also included a few photos for use with the article. The first photo is mine from a hunt for white tailed ptarmigan in Alaska’s Kenai Mountains with my English setter, Winchester. The second is the stamp group photo, courtesy of Ultimate Upland and Prototype Stamp Artist Shari Erickson.

[Continue the conversation on the Upland Stamp Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/groups/1555537004709382].

Christine Cunningham is a lifelong Alaskan, author, and outdoor columnist known for her contributions to outdoor magazines and her commitment to creating opportunities for women to connect and share their stories. Her first book, “Women Hunting Alaska,” profiles some of Alaska’s most outstanding female hunters.

Christine Cunningham is a lifelong Alaskan, author, and outdoor columnist known for her contributions to outdoor magazines and her commitment to creating opportunities for women to connect and share their stories. Her first book, “Women Hunting Alaska,” profiles some of Alaska’s most outstanding female hunters.

Comments