Three Ways to Add Variety to Your Russian Capercaillie and Black Grouse Hunt

Although capercaillie and black grouse are the highlights of the Russian spring hunting season, other game birds are also legal that time of year including geese, ducks and woodcock.

The Russian spring season on geese is very much open and is an extremely popular affair. Hunting is done in the traditional manner, from blinds with decoys on the fields where the birds feed. However, the caveat is that wide open spaces that make good resting stations for migrating geese are seldom located anywhere near good grouse habitat in case you’re interested in adding them to your bag.

The Russian bean goose.

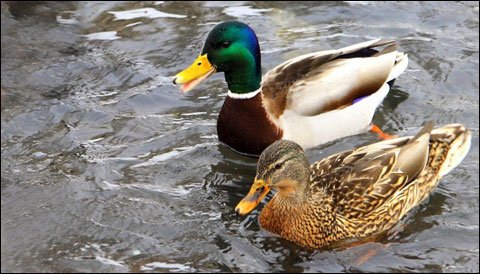

For ducks, it’s easy to find a nice lake, marsh or flooded river bed on the preserve where you hunt black grouse and capercaillie. Here you may have a chance to participate in the ancient tradition of hunting with live decoys. This is not the exterminating market hunter’s slaughter you’re probably thinking about – tough restrictions are in place to make sure only a very limited number of only male birds is harvested.

The Russian live decoy duck at work is a sight to behold. It is much more than an animated quacking dummy – its goal is to attract sexually obsessed drakes who are on the lookout for loose females, and it pursues it very actively. In fact, enthusiasts breed them like pointers. In any case, a blind in good near-water habitat is a nice place to be for its own sake – opportunities to observe Russian wildlife are innumerable, and a drake or two, in their magnificent spring plumage, will add a nice touch to your experience (and dinner table).

The ancient tradition of hunting with live decoys is still alive in Russia.

Woodcock was a favorite bird of every great Russian writer who was a sportsman, and the spring mating flight was their favorite way of taking them. Every evening woodcock males go looking for females by flying low and slowly, with peculiar “tsk”-ing sound, along edges of the wood, clearings, or tracks, and you simply wait for them in such places. No blind or call or sophisticated camouflage is necessary. Open your “Anna Karenina,” flip to the part where Oblonsky visits Levin at his estate, and you’ll find perhaps the best description of what it’s all about.

Woodcock mating flight is the opposite of a driven grouse shoot. There’s no fear you’re going to burn your fingertips off the barrels – an evening when you get to see a dozen of mating males in range is legendary, and two birds per day is considered a decent bag. The main attraction of this hunt is the poetic atmosphere of a forest in spring. Dusk, as every hunter knows, is the most animated time in any habitat – the day dwellers harry to finish their affairs and settle for the night, while the nightly birds and beasts rise from their slumber to tether for whatever their business may be. And you’ll find yourself right in the middle of this action – with a wide variety of songbirds providing the soundtrack. Just being there is a rare treat.

Waiting for woodcock’s evening mating flight is often described as Russia’s “most poetic hunt.”

Good grouse habitat is usually rich in woodcock too, and the action takes place in the evening, not in the morning, so this “most poetic of Russian hunts” combines well with your adventure. Waiting at the edge of a forest to hear the mysterious mating call of the “woodland snipe,” like the noble characters of Tolstoy and Turgenev is an opportunity you simply don’t want to miss.

Aleksei Morozov grew up dreaming of the outdoors in a polluted Soviet industrial town, and relishing every opportunity to go hunting and fishing with his father and grandfather. After a few years of teaching English and Linguistics at a university, he followed his heart and became an outdoor writer. Aleksei’s stories appeared in the Russian edition of Sports Afield, the Russian Hunting Magazine (where he won the Writer of the Year award in 2014 and 2015), and other publications. Now he runs the blog and social media pages of www.bookyourhunt.com

Aleksei Morozov grew up dreaming of the outdoors in a polluted Soviet industrial town, and relishing every opportunity to go hunting and fishing with his father and grandfather. After a few years of teaching English and Linguistics at a university, he followed his heart and became an outdoor writer. Aleksei’s stories appeared in the Russian edition of Sports Afield, the Russian Hunting Magazine (where he won the Writer of the Year award in 2014 and 2015), and other publications. Now he runs the blog and social media pages of www.bookyourhunt.com

Comments