Shooting Sporting Clays With The Ghost of Johnny Reb

The opportunity to shoot sporting clays on hallow ground doesn’t present itself that often, but you can do it in the area of Manassas, Virginia where the battles of Bull Run were fought.

Depending on which side of the Mason-Dixon Line you’re standing, it’s called either the First and Second Battle of Bull Run (as it’s known in the North) or the First Battle and Second Battle of Manassas (the Southern name for it). The first battle took placed July 21, 1861 while the second, larger battle was fought August 28-30, 1862.

The confrontations bore the hallmarks of great struggles. They served as theaters for the Confederacy’s best military commanders: Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, Robert E. Lee and James Longstreet.

The First Battle of Bull Run was the earliest major land battle of the Civil War.

The South’s First Big Victory

Union troops under Brigadier General Irvin McDowell advanced across Bull Run against the Confederate Army under Brigadier Generals Joseph E. Johnston and P.G.T. Beauregard. It proved to be the South’s first major land victory in which the Union Army was forced to withdraw to Washington, D.C.

Bull Run was also the battlefield where a certain Col. Thomas J. Jackson of the Virginia brigade came to be known as Stonewall for standing his ground — although some experts believe it was a pejorative because he was unresponsive to Confederate General Barnard Bee who needed Jackson’s support.

Whence Came the Rebel Yell

What you may not know about Jackson is that he also went down in history for giving Union soldiers their introduction to the blood-curdling Rebel yell…

Pressing his attack, Jackson ordered “Reserve your fire until they come within 50 yards. Then fire and give them the bayonet. And when you charge, yell like furies.”

In the end, nearly 900 soldiers died on both sides, with some 2,700 wounded and 1,300 missing or captured in the First Battle of Bull Run.

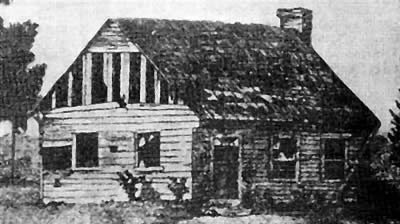

One notable civilian casualty of the First Battle of Bull Run was the 85-year-old-widow,

Judith Carter Henry. An invalid, she was confined to her bedroom in the Henry House near the battery of Southern artillery. When Captain James B. Ricketts of the Union’s artillery division believed he was under fire from the house, he turned his cannons to the building, making a hit on Mrs. Henry’s bedroom. She died later that day from the wounds.

The Second Battle of Bull Run was the climax of an offensive campaign by Lee against the North. Jackson and Longstreet had trapped the troops of Union Major Generals John Pope and Fitz John Porter — forcing them to retreat into a barrage of Confederate cannon fire on the battlefield of Bull Run. The assault by the Confederacy proved to be the largest of the Civil War — with both battles victorious for the South.

After the smoke cleared on the Second Battle of Bull Run, the Union Army counted 10,000 killed and wounded out of 62,000 engaged, while the Confederates lost 1,300 lives and 7,000 wounded out of 50,000.

The Henry Loop Trail

The places where these battles were fought are now called the Manassas National Battlefield. The 5,000-acre park encompasses the ground of the two major battles.

We walked the Henry Hill loop trail. It’s a mile long with recorded messages and signs relating the history of the First Battle of Manassas.

You could also hike the First Manassas five-mile loop trail, which traverses where the battle of July 21, 1861 was fought.

The Second Manassas five-mile loop trail covers the significant points of the three-day battle. The park also features other driving and walking tours.

The park is exceptionally touching because little has changed since these battles were fought. On the day we visited the smoky, wintry sky served as a solemn remembrance of the misery endured here nearly 150 years ago.

Before we left, we turned to give Bull Run one final look. The hills rolled out before us like a landscape painting. The pastoral vista seemed cured of the mayhem and bloodshed, but somehow you wonder if the land will ever be at peace with itself.

We returned to the car, and then took a 6½ mile drive northeast to the Bull Run Shooting Center in Centreville, Virginia, where the Union Army was making its retreat, during the First Battle of Bull Run, on its withdrawal to Washington, DC.

At first glance, the Bull Run Shooting Center seems like the dream of every shotgun owner.

Managed by the Northern Virginia Regional Parks system, the Bull Run Shooting Center features sporting clays, skeet, trap, wobble trap and 5-stand. The facility seems to be in tip-top shape. The club house even had a roaring wood fire warming up the place on the chilly day we visited. And if you’re into archery, there’s an indoor target range with 18 lanes.

Unsafe at Any Speed

So what could go wrong?

Well, it was one of the most unsafe places we’ve ever shot.

Now don’t get us wrong, we’re all for new shooters. But there was a preponderance of them that particular day and they acted absolutely clueless about the basics of shotgun safety.

Each skeet field has a trapper, and they all seemed overwhelmed by the sheer number of new shooters. After skeet, we opted for 100 rounds of sporting clays. We were appalled that at the first station, our trapper let one of our squad members shoot without eye protection. We had to bring it to our trapper’s attention, and even then it took another trapper who was within earshot to approach the offending shooter.

In the same vein, we had a straggler join our squad. This guy came right up to station 1 also without eye protection — once again without a reprimand from our trapper.

The sporting clays course has 14 stations. It’s actually designed for 50 shots, but if you shoot 100, you end up shooting about 8 targets per station, which turned out to be a bit excessive.

Long, Elusive Targets

When it comes to sporting clays, maybe we’re purists. We think that sporting clays should present targets that you would normally encounter as a wingshooter. That means you don’t deliver a series of 50- and 60-yard targets — especially beginning with the first station.

Shouldn’t the first few stations be warm-ups? The kind of targets that let you swing the gun the bit, get your eyes acclimated, give you a chance to settle into your gun mount?

Not according to the Bull Run Shooting Center.

Station 1 delivered a screaming simo pair. The closest target was about 30 yards, the furthest easily 50-60 yards.

Station 2 presented a looper with a quartering away target that also must’ve been 50-60 yards.

Into the Woods

By station 4 we were in the wooded area. This presented a new set of problems that really had nothing to do with the target set-ups.

The bare trees were very dense, but not quite enough to cover the gray sky. Take into account the thousands of vertical branches and it was like having a bar code as a backdrop: imagine trying to focus your eyes on the target.

As we progressed along the course, our trapper proved useless. If a target broke coming out of the machine, he never called it a broken bird: he didn’t have a clue. We asked his advice on how to shoot a tricky simo pair and he said he didn’t know. And it was up to the entire squad to make sure everyone was in place to see the lookers, otherwise the trapper just would’ve pulled them regardless of who was able to see them.

Maybe if we had gone to the Bull Run Shooting Center on a different day, at another time of year, the crowd would’ve been different, and certainly there would’ve been leaves on those darn branches.

But if you find yourself in the area, you should definitely visit the Manassas National Battlefield Park. It is there, rather than the shooting center, where you’ll truly find something to behold.

Deborah McKown is the editor of Shotgun Life. For questions or comments, please send your email to letters@shotgunlife.com.

Useful resources:

http://www.nps.gov/archive/mana/home.htm

http://www.nvrpa.org/parks/bullrunshooting/?pg=shooting.html

Deborah McKown is the Editor of Shotgun Life. Please send your comments and questions to letters@shotgunlife.com.

Comments