48 Hours at Griffin & Howe’s Exquisite Hudson Farm Day 2: Shooting a Fabbri, Boss, Purdey and Anderson Wheeler

As September approaches, in our secret heart every shotgun disciple anticipates their annual pilgrimage to a beloved place. For some of us it’s the autumnal woods of Maine for woodcock, a goose hunt on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, sporting clays at The National Shooting Complex in San Antonio or maybe throwing clays from that rusty hand-loader at a family barbeque. Personally, that special journey takes me to Griffin & Howe’s gorgeous Hudson Farm in Andover, New Jersey.

So in September 2015 we visited Hudson Farm for 48 hours to see friends, sharpen our sporting clays skills and shoot magnificent shotguns. On the first day, Griffin & Howe’s lead instructor Kevin Sterk handed me a lovely old Boss side by side for lessons and we rode the knobby-tired golf cart up through the wooded path to the station that Griffin & Howe clients use to rehearse high birds usually before flying overseas for a driven hunt.

Come the second day, we shot some of the world’s best shotguns on the Hudson Farm sporting clays course.

The four beauties laid open on the presentation table in the Pro Shop at Griffin & Howe’s Hudson Farm: the Boss, the Fabbri, the Purdey and the Anderson Wheeler. Around us in meticulous displays tweeds, leather, waxed jackets, new shotguns and accessories mingled in a depiction of the estate sporting life.

This bucket-list selection of four used shotguns valued at some $200,000 can, in fact, stir a sense of dread. Not because of the lofty prices that cause hyper-vigilance when handling them; the deeper foreboding is a subconscious deprivation that will nibble at your soul whenever reaching for your go-to shotgun. Boss, Fabbri, Purdey, Anderson Wheeler – they’re the sporting gun equivalent of a one-nighter with Sofia Vergara, Kate Upton, Jennifer Lawrence or Heidi Klum.

Both species of exotics can change a guy’s life forever. Sure that Caesar Guerini is okay, but after shooting a $58,500 Fabbri also from Italy there’s a haunting withdrawal that rationalizes itself away during our daily routines but never completely departs.

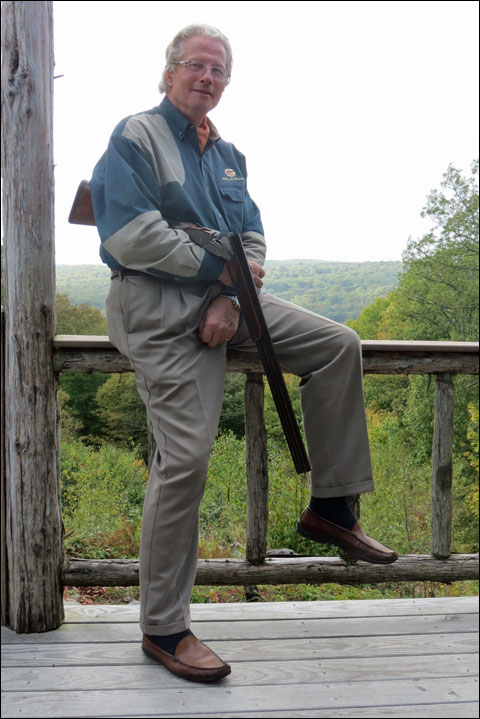

The schedule for day two at Griffin & Howe’s Hudson Farm called for sporting clays with these extraordinary shotguns, accompanied by CEO, Guy Bignell. Since my last visit, the course had been dramatically expanded into the upper reaches of dense woods where targets grow progressively difficult.

Griffin & Howe CEO, Guy Bignell, at one of the high stations on the Hudson Farm sporting clays course.

Another bright Indian Summer morning secreted musky fragrances of impending autumn around the 4,000 acres of woods and understory. I wanted to re-experience the pleasure of that old Boss side by side from yesterday’s lesson with Kevin Sterk. With Mr. Bignell clearly in charge of the off-road cart, we rode past the occasional turn-of-the-century outbuildings now converted to lodging and stopped at a sporting clays station of stone and timber on the lower Novice Course.

The single-trigger, 12-gauge Boss built in 1965 had a straight grip, custom beavertail forend and flat rib. Case colored sideplates complemented by a matching long trigger-guard tang showcased classic rose-and-scroll engraving. The walnut colorations were of barrel-aged single malts. With 26-inch barrels, the gun is probably thought a bit unfashionable as longer seems better these days. Certainly a notion to reconsider since at 6 pounds, 9 ounces the Boss moved with aristocratic grace.

Boss & Company is synonymous with single trigger guns, whereby one trigger can fire both barrels one after the other on a double barreled gun. John Robertson’s work on the single trigger in the 1890s is probably the last development of importance that occurred in sporting shotguns.

Boss has perfected the single trigger more than any other maker and is still regarded as the leading manufacturer of single trigger guns due to their reliability and performance.

The Boss shot by the author on the Hudson Farm sporting clays course.

And that heritage of innovation translated into a beautiful overall shooting experience.

For a moderately light 12-gauge side by side with a checkered butt the shotgun exhibited muted felt recoil. The gun’s inherent nature was buoyancy – effortless motion and trigger. It’s the intangible mystique of rarified price points in the world of best shotguns. The engraving, wood grades and meticulous craftsmanship are all expected from the likes of a Boss where new shotguns hover around $100,000. The ethereal, though, is realized when shooting it becomes an expression of joy – not just enjoyment as most us know with our favorite shotguns – but an effervescence of the heart.

Back in the cart, we charged up the pastoral path to the intermediate 10-station Scenic Course. Targets here flew quicker and further − some stretching away from elevated shooting platforms across the forested hills and valleys.

Priced at $110,000, the 12-gauge Purdey sidelock belonged to a pair numbered 3 and 4. The double-triggered side by side looked exceptionally clean. Completed in 1933, the guns were built to the same specifications as an earlier pair for Philip Cunliffe-Lister, 1st Viscount Swinton of Masham and the Baron Masham of Ellington, of British peerage. Guns number 1 and 2, built separately from 3 and 4, were apparently lost by the family during or just following World War II. In 2003, the shotguns had been re-stocked by Purdey with exhibition grade walnut and checkered butt on the straight stock. Case-colored sideplates displayed Purdey’s customary fastidious rose and scroll pattern. Twenty-eight-inch barrels were choked skeet/skeet. At 6½ pounds, it communicated the ideal weight for a game gun.

The author shot gun number 3 of this match pair of Purdeys.

Mr. Bignell pulled targets and stuffed shells. With his British accent and Purdey in-hand, well, I was almost at Windsor Royal Great Park. The Purdey moved differently than the Boss. It felt better suited to plump pheasants over dogs than the twenty-first-century, jet-fueled, quartering clays that sliced across my view. Although the Purdey weighed a few ounces less than the Boss, its stature was more established, less impetuous, somehow wiser, not impulsive enough to chase those silly orange saucers. The Purdey seemed to understand what’s best for the both of us.

Going from a centuries-old legacy to one in the making, I reached for the London-made Anderson Wheeler SLE 20-gauge side by side.

Not familiar with the marque?

The gun and rifle maker was started in 2006 by professional hunter Stuart Anderson Wheeler. The company’s compact Shepherds Market store houses their firearms as well as quality fly fishing gear, clothing, accessories and luxury travel.

The 20-guage Anderson-Wheeler in action on the Hudson Farm sporting clays course.

Anderson Wheeler is still regarded as a relatively new London gunmaker and luxury goods firm. Each shotgun takes approximately 12 months to custom build.

As a big-game hunter and guide, Mr. Anderson Wheeler lives and breathes firearms dependability. Although the receiver and barrels are commissioned, triggers originate from in-house CNC machines.

The reinforced boxlock action is hand-engraved with Anderson Wheeler’s trademark bold foliate scroll on either a coin or case-colored finish. On the gun I shot, the contrast between eye-catching bright sideplates and smoky figuring in the maple-hued walnut gave the Anderson Wheeler a flash of nouveau élan.

The 6¼-pound side by side was fitted with 29-inch barrels choked improved modified/extra full. Given the tight constrictions we decided on the high, far birds of a station up the hill.

One of the spectacular vistas from the Hudson Farm sporting clays course.

As I entered a platform of rough-hewn timbers the outlook presented a blanket of treetops and pastures that reached the horizon. No trap machines in sight meant that my skills would be stretched – or as Gil and Vicki Ash say, my peripheral acceptance (a shooter’s comfort zone for target leads) would be pushed to the limit (and please no excuses about shooting a 20 gauge).

From the ready position the Anderson Wheeler felt balanced and adept – ready to go. Mr. Bignell pulled targets that demanded pushing the envelope on forward allowance. The shotgun moved with satisfying poise and yet I had to extend the lead further and further shot after shot at the urging of Mr. Bignell. I’d like to believe that it was more persistence than luck after the first clay broke. But a rhythm had finally been attained and break points determined to the extent that the Anderson Wheeler broke more targets than missed. It helped that the triggers had zero creep – one less complication – with an intuitive pull that contributed to consistent timing. In the end, that lovely 20 gauge also proved mighty.

The Fabbri from the Griffin & Howe gun room.

It was pure coincidence that brought the Fabbri to the Scenic Course – the highest and most challenging at Hudson Farm. While opinions may collide over which is the best British gun, when it comes to the Italians that argument is likely to concern Fabbri, Bosis or Bertuzzi.

The Fabbri family makes about 20 guns per year from a space-age factory in Brescia, Italy whose computer-controlled machines yield aerospace tolerances. Craftsmen hand finish the wood, engraving and ultimately the final fitting of components. These are investment-grade gems that new cost about $200,000.

So I’m on a mountain-top sporting clays stand with a pastoral panorama holding a used Fabbri Best priced at $58,500 – a dreamy occurrence for any wing and clays enthusiast.

The 12-gauge over/under had 28-inch barrels choked full/improved modified. Its single trigger, slender forend and straight English grip worked in concert to control the finely balanced 7½ pounds.

As the long targets soared over the terrain, the Fabbri conveyed an aeronautical precision. The wide swings moved with gyroscopic stability across the horizon. Again, it took several attempts to decipher the long birds and the Fabbri’s sensibility was muse-like in reading the targets. In motion, the shotgun felt closer to 7 pounds and maybe the decisive, smooth trigger contributed to the lighter impression.

The final shot of the day had been fired – punctuating an incredible 48 hours at Hudson Farm.

(For the first part of this series visit Shotgun Life at http://bit.ly/1JVpPf8.)

Irwin Greenstein is the publisher of Shotgun Life. You can reach him at contact@shotgunlife.com.

Useful resources:

Irwin Greenstein is Publisher of Shotgun Life. Please send your comments to letters@shotgunlife.com.

Comments