How Shotgun Engraving Inspired Beautiful Belt Buckles: A Conversation with Neil R. Hunt

The sunsets of Sedona, Arizona draw seekers in pursuit of their own personal spiritual enlightenment to the fiery glow cast on high-desert rock formations. That haunting splendor is a monument to the local mystical soup of Native American beliefs, New Age transcendence and self-proclaimed UFO refugees. As a hot spot of awakening and harmony, Sedona is a natural home to artists who draw inspiration from the beautiful gods of the harsh, majestic landscape.

Neil Hunt’s arrival in Sedona came shortly after the global phenomena called Harmonic Convergence – the late 1980s, planet-wide introspective that coincided with extraordinary planetary alignment of the Solar System. And it was here, through his own personal quest, that he discovered how the ancient scroll pattern of so many shotguns can be applied to his hand-crafted belt buckles of silver and gold.

“I told myself back then that I needed to learn to engrave like those old gun engravers,” he said.

Neil Hunt at the bench of his studio in Sedona, Arizona.

The collective consciousness of Sedona is rich with symbols and myths, but it was the ancient acanthus scroll that captured Mr. Hunt’s imagination. The acanthus is actually a pervasive plant of the Mediterranean. In classical Rome and Greece it flourished as architectural embellishments where the motif symbolized enduring life and immortality.

How long the acanthus has been adorning firearms is up for debate, but the engravings have been documented in the U.S. as far back as the Kentucky Long Rifles of the mid-1700s. Some 100 years later, firearms engraving had reached a Golden Age. Fine doubles from England served as canvases for images of sport hunting and commemorative events in a tradition that continues today.

This beautiful Purdey shows the classic acanthus scroll that inspired the designs of belt-bucker engraver, Neil Hunt.

“For the most part, I don’t think a day goes by that I don’t spend studying the old double guns,” said Mr. Hunt, who added that most customers for his buckles are indeed owners of fine long guns.

His attraction to the decorative arts started long before he landed in Sedona. Born and raised in Northern Minnesota, he had been studying, making, and appreciating art since age five as a means to express himself in “a culturally deprived town,” he recalled. His parents encouraged him with a particularly poignant gift: a big book of Michelangelo drawings that he used to teach himself the art of the pencil.

It was his wife’s uncle, though, that “flipped me from fine arts to ornamental arts,” according to Mr. Hunt.

His wife is Norwegian and they married there in 1984. During their honeymoon the newlyweds hiked through the rugged countryside, making a stop at the farm of her uncle, Ragnvald Frøysadal, atop a mountain in the Gudbrandsdalen valley.

Ragnvald Frøysadal making a bowl on his farm in Norway.

“We walked out of the wilderness into their farm,” related Mr. Hunt. “Tori’s aunt and uncle had a house and some log cabins. Ragnvald was outside carving a bowl and I walked up from behind and I just saw this idyllic scene of him working on the bowl. I was just taken by it. I started asking questions. He didn’t speak English very well and I didn’t speak Norwegian very well.”

Despite the language barrier, Mr. Hunt was about to experience a turning point in his career.

“Ragnvald ran behind the barn and got a thistle weed and twirled it very slowly,” Mr. Hunt continued “It was his way of telling me about the acanthus scroll − the root of all the beautiful curves in engraving. And in his case it was carving bowls.”

This belt buckle by Neil Hunt clearly shows the acanthus influence sparked by his early relationship with Ragnvald Frøysadal.

The Hunt’s spent about a week at the Frøysadal farm learning about the acanthus and the decorative arts.

“He shared his enthusiasm for decorative acanthus scroll work with me many times,” Mr. Hunt said. “Ragnvald mentored and inspired me in the engraving skills, and in the decorative arts’ design process. He did incredible engraving on knives and sheathes and I realized that I wanted to do that with belt buckles. That flip from the fine arts to the decorative arts, it almost happened in a moment.”

They subsequently returned several times to visit the farm – the trips an ongoing learning experience for Mr. Hunt. He wanted to engage in an apprenticeship with Mr. Frøysadal, who unfortunately died before it could begin.

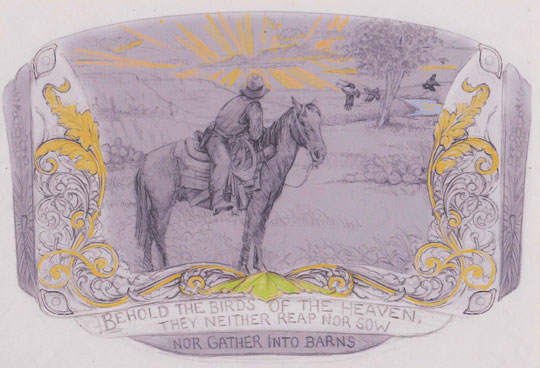

Acanthus and birds reflect Neil Hunt’s inspiration from fine shotgun engraving on his own belt buckles.

Making that transition from fine artist to engraver would involve some the basic tenets of carpentry that Mr. Hunt learned from his father.

“My father taught me the value of traditional craft work and the sense of connection and satisfaction that can be derived from working with your hands,” he recalled. “He was my Zen master.”

Neil Hunt’s earliest skills as a fine artist continue to play a significant role as

he draws studies for belt buckles before actually making them.

As young man, Mr. Hunt had traveled the Dakota prairies with his father in a 1957 Bookmobile converted into their camper and work truck “going from job to job,” he recounted. “Worked on isolated jobs that didn’t have good, or a lot of craftsmen. The front of the truck was fixed up like a camper and we stayed on the job until it was done. We approached our work philosophically and we enjoyed it. Carpentry was a family tradition for generations and I found it to be a valuable extension of my arts training.”

Perhaps the most important lesson Mr. Hunt learned from those years was “That experience taught me work ethic,” he said. “One of the keys to my success as an artist is a solid work ethic.”

Returning from Norway, Mr. Hunt and his wife moved to Sedona. He intended to become a cabinet maker, but instead started working with a friend who owned a belt business.

“At the time I thought they were expensive belts,” he said. “The belts were hand-stained harness leather with turn-of-the-century, gunstock-like embossing. We supplied Bloomingdale’s, Macy’s, Neiman-Marcus, and the like. These belts had a blend of Eastern simplicity and American Western design. While designing for this line I was inspired by the incredibly fine and beautiful workmanship in old weaponry.”

A pheasant in flight on a belt buckle by Neil Hunt.

That venture was short-lived and afterwards Mr. Hunt decided to start his own belts in 1985, opening the doors to NR Hunt Studios.

“I soon realized that would require learning to make my own buckles,” he explained. In the meantime, he supplied leather straps to custom buckle makers who generally practiced the styles of Western, Southwestern, Southwest Indians and even high fashion.

He was first impressed, though, by the bright-cut Western engraved buckles.

Neil Hunt’s fondness for Western belt buckles as depicted in his pencil

rendering titled “Cowboy Sunset.”

His belt partner went out of business, giving Mr. Hunt the impetus to create his own belts and buckles initially inspired by cowboys and Indians.

“I admired the bright cut engraving you see on cowboy belt buckles,” Mr. Hunt said. “It’s the epitome of fine craftsmanship. I wanted to learn how to engrave that way.”

The endeavor would require that he learn silversmithing and improve his engraving talents. Yet again, Mr. Hunt would meet a man responsible for teaching him vital skills – Franz Marktel.

An Australian, Mr. Marktl had already established a reputation in the U.S. for being one of the tops in his field. Under his tutelage, Mr. Hunt learned the deep-cut, Germanic style of engraving. Always a student of engraving, Mr. Hunt more recently participated in the GRS Grand Masters Program – a 12-day symposium in Emporia, Kansas, where his instructor was the famed Amercian engraver, Winston Churchill. The annual event brings together the finest engravers for discussions, lessons and demonstrations.

Mr. Hunt also studied with one of the most famous shotgun engraving studios in the world: Creative Arts of Italy.

For Neil Hunt, engravings for his belt buckles always start with a drawing.

Still, Mr. Hunt continues to rely on his gift of drawing developed as a youngster. He uses pencil and paper to sketch out ideas for buckles – those drawings often works of art unto themselves.

“I’m 60 years old now,” Mr. Hunt confessed. “I’m getting to the point in my life where I feel like I’ve reached some culmination. I feel like it takes so long to do this well. And there’s only so much you can do before your body parts give out.”

He laments the notion that “the decorative arts are dying. There’s so much plastic and shallowness in our lives today. I see it ending, not just with me, but the whole long chain of 2,000 years. We’re losing our sensitivity to it. But those old shotguns…”

Irwin Greenstein is the publisher of Shotgun Life. You can reach him at contact@shotgunlife.com.

Useful resources:

Irwin Greenstein is Publisher of Shotgun Life. Please send your comments to letters@shotgunlife.com.

Comments