Shotgun Lust

It’s an autumn afternoon in southern New Jersey and I’m in a luxurious tent browsing the best shotguns, when something different, beautiful, stunning catches my attention.

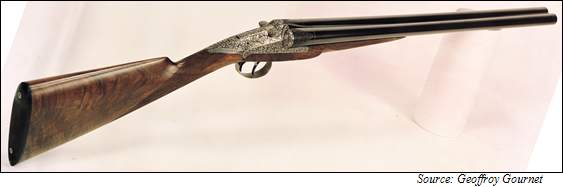

The side-by-side is held in a tall vice by its trigger guard — the clean contour of the receiver evocative of a 1967 Corvette Stingray fastback. I have to see this gun up close.

I squeeze through the round banquet tables now empty after a gourmet lunch. A few stragglers share conversation, but their voices are an afterthought as I approach this marvelous shotgun.

Now that I’m standing next to it, I realize that the shotgun is in-the-white — the stainless-steel appearance forward-looking yet faithful to the side-by-side pedigree.

The breech is slid open, the lever that operates it raised like a Crucifix displayed in a jeweler’s case.

Mesmerized by the design, it dawns on me that the barrels don’t swing down. You load the shotgun by sliding back the breech with a lift of the lever, then push down the lever to close it.

The streamline action flows into a straight stock void of the heavy figuring that could detract from the elegant silhouette.

The shotgun could easily stand on its own in the Museum of Modern Art in homage to industrial design along side a 1937 Bugatti Drop Head Coupe, an Eames-Saarinen potato-chip chair or a Caran d’Ache “1010” fountain pen.

The thin, neat man behind the table is being very patient, giving me ample time to admire the shotgun.

“What is it?” I ask.

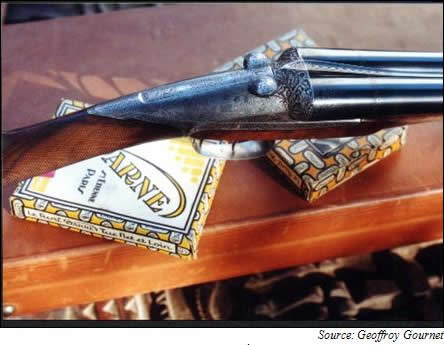

“It’s a Darne,” he says with a French accent, the “e” silent.

I study the Darne with great reverence. The air is perfumed with wood smoke and autumnal mulch of bird-hunting season. It’s all very tempting.

The venue for this shotgun epiphany is picture perfect: Griffin & Howe’s luxurious Hudson Farm Shooting Grounds.

The shooters have now returned to the sporting clays course, and I realize that with no prospective customers around perhaps this French gentleman can spare me a few minutes. We sit together at an empty table for a cup of coffee.

His name is Geoffroy Gournet, and he tells me that he is now the exclusive U.S. importer of Darne shotguns.

It’s ironic that I marvel at the shotgun’s seductive design while its in-the-white. Because Mr. Gournet is a world-class engraver. As you listen to his story, you realized that he and the Darne were destined for each other.

He tells me that he came to the U.S. from France via Italy.

He had graduated from the Belgian School of Gunsmithing in Liege, where he was awarded The First Prize of Basculage for his work. With ambitions to learn from the Italians he later served in the workshops in Gardone Val Trompia with such masters as Ceasare Giovanelli, Gianfranco Pedersoli, Julio Timpini, Giacomo Fausti and Giovanni Steduto.

In 1985, after became a Master Engraver, he emigrated to the U.S. He landed a position as the only full-time engraver at Parker Reproduction, where he stayed for 15 years working exclusively on the custom A1 shotguns.

Now a freelance engraver, he lives in Easton, Pennsylvania, about 65 miles south of New York City.

I pay close attention to Geoffrey, but I have to admit that my eyes are drawn to the Darne that floats in the vice over his right shoulder.

“How did you start importing Darnes?” I ask.

He explains that he had already been performing restorations on Darnes here in the U.S. An avid cyclist, he returned to France in 2004 for a bicycling trip and took the opportunity to visit the company. Six months later, they called to see if he would represent them in this country. Today, his Darne business is so successful that customers face a backlog of 6-12 months for the shotguns that start at $6,500.

What I find most remarkable about the Darne is that the shotgun has not fundamentally changed since 1893, when Regis Darne designed the R model sliding-breech, fixed-barrel shotgun in Saint Etienne, France.

Regis’ son, Francisque, had left his father’s company in 1983 to form his own company, F. Darne Fils Ainé also in Saint Etienne. Francisque died in 1917, but through a series of four owners the company remained in production until 1955.

In 1981, a former head of the Darne workshop named Paul Bruchet bought the inventory and machines to resume production of these spectacular shotguns. Bruchet was able to incorporate many of the parts made 50 to 80 years ago left sitting in the factory. He also took the opportunity to refine the original design. For instance, he added a metal rod inside the stock to add rigidity.

Legal constraints forced him to abandon the Darne name and manufacture the guns as Bruchets. But by the early 1990s, he was to resurrect the Darne marque that remains in force today. After Paul Bruchet retired, his son Herve continued the family businesses and makes the guns that Geoffrey imports.

In a way, it’s amazing that this unique shotgun has endured for 115 years. You expect it from the traditional break-open shotguns such as Holland & Holland, Purdey and Boswell.

It’s the sliding breech of the Darne, however, that endures alone in the hearts of a few adherents.

Take Rich Beck of Connecticut. A Darne owner and collector, he no longer trades his beloved Darnes; instead, he keeps them for his own enjoyment.

Rich fondly recalls how he bought his first Darne about 20 years ago. He had lived in Connecticut back then, long after his parents had moved to Cape Cod. Driving to visit them, he made his customary stop at a little gun shop in Massachusetts. That’s where he saw his first Darne. He had heard about them but this was the first one he ever laid eyes on.

At the time, he was a policeman making $5,000 a year, and of course paying $1,400 for a used shotgun qualified the Darne as a fanciful indulgence. Although he couldn’t afford the gun, his passion was ignited.

“The gun kept haunting me,” he said. “I kept thinking about it, and I kept telling myself ‘I got to have that little guy.'”

He embarked on intensive research of the gorgeous French shotguns.

Each visit to his parents brought a stop to that gun shop, until after several months Rich was able to get the price down into his range. He has since owned seven Darnes, of which five were traded to upgrade. He currently owns two Darnes, a P17 and an R15.

I asked Rich what was it was like for him to shoot a Darne.

“The length of pull is a little short, and the stock has a little more drop, so you have to keep your head down on the gun. If I pre-mount the gun, and keep my head down I do really well. If I shoot from the low ready position I have to concentrate more. Darnes are very, very light and it’s easy to over-swing in a sustained lead. But the best part is that you can carry it all day. It’s a joy to carry. The balance is above average. The feel of the Darne is light at the front and quick to point. You pick up a Darne and you’re amazed at the feel.”

Over the years, Darne built four variations of its sliding-breech, fixed-barrel shotguns: The R series, the Halifax, the P series and the V series. All were monoblocks, mostly with two triggers.

As with all Darnes, the grade is shown by a series of stampings under the barrel. After you remove the barrel, you look at a flat section on the bottom where you’ll find a number of grade stamps. You count the number of stamps, add 10 and you have the grade number; the higher the number of the stamps the higher the grade of the shotgun.

The R was offered in grades R10, R11, R12, R13, R14, R15 and R16. They were available in 12- and 16-gauge models. There was a custom R called the RHS. In addition, Darne manufactured a double-express rifle up to .455

The short-lived P used some of the advanced action of the V, making it the mid-range model. It picked up where the R left off, coming in grades 17 and 18. The P used the frame of Darne’s premium V model, but many lacked the double triggers and full-coverage engraving.

The V is the best that Darne has to offer. It begins at grade 19 and can go up from there. Like the R, it’s also available in a custom model called the RHS. The V’s Holland & Holland action includes double sears. The V was also distinguished by its extractors, larger breech lever, hidden top-lever pin and articulated triggers.

Darnes weighed in at between 5½ and 6½ pounds, with the Halifax pushing 7 pounds. All were proofed in St. Etienne. Constrictions and barrel lengths varied, but duck hunters loved the Darne because its fixed barrels made the shotgun a breeze to load in tight quarters where you needed to keep the muzzle aimed outside. The Darnes were also maneuverable thanks to their light-weight hollow rib, also called a “canon plume” or “feather barrel,” which tapered down at both ends of the barrel.

Darnes started entering the U.S. during the 1950s and very early 1960s through two importers: first Firearms International of Florida and then Don White of Michigan. After Don White, Stoeger Arms of New York.

It was during both World Wars that Darne created a low-end R called the Halifax — the design licensed out to different manufacturers. With the Halifax, Darne was able to use its entire surplus inventory from the 1930s and 1940s in a single model. Although the Halifax was assembled from excess parts, the quality remained quite high. The Halifax has been out of production for decades.

Very few Halifax shotguns made it into the U.S., with the exception of a few GIs bringing them back from Europe.

After World War II, Darne introduced several new R models.

The top-of-the-line R Prestige was distinguished with a plume rib, large key-shaped handle on the lever, double sears and high-grade walnut. It featured full-coverage engraving. It could be ordered in 12 or 16 gauges.

Next, the R Ambassadeur had a large key-shaped handle on the lever and double sears. The breech received a gray finish and good quality walnut. It was available in 12 and 16 gauge.

Darne’s R Rambouillet was available in 12 and 16 gauge. It also had a the large key action. The walnut was select quality. The case-hardened receiver got light engraving.

The R Gouverneur came in 12, 16 and 20 gauge. The engraving was in line with the shotgun’s lower price. It had a similar receiver and stock as the Ambassadeur. Likewise, the Gouverneur Plume and Plume Magnum were essentially a Gouverneur with a plume rib.

The Darne R Baronnet-Broussard was manufactured in 12, 16, or 20 gauge models. It had a lightly engraved receiver with a satin chrome finish. It was of a lower quality than the Ambassadeur.

Next down the line was the R Classic. Available in 12 and 16 gauge, it lacked engraving. The stock was plain wood.

Darne’s post-war R models maintained a weight of 5 to 6 pounds with barrels that averaged 27 inches. To this day, they remain nimble, reliable shotguns ideal for upland shooting.

Today, Geoffroy imports Darnes in both the R and V models. The V starts at $15,000, while prices for R begin at $6,500. They are available in all standard bores, with single or double triggers and just about any grade wood. Darne double rifles are also still in production up to 9.3X74 and .375 Holland & Holland Magnum.

Most of the Darne shotguns today are bespoke, but Geoffroy tends to stock just a few for people who fall in love at first sight.

Noe Roland is a contributor to Shotgun Life. Please direct comments and questions to letters@shotgunlife.com.

Useful resources:

http://gournetusa.com/darneusa/new_page_1.htm

http://www.griffinhowe.com/thefarm.cfm

Comments