Hemingway’s Guns: The Sporting Arms of Ernest Hemingway

Our friend Silvio Calabi gave us a heads up that the book he co-wrote called “Hemingway’s Guns: The Sporting Arms of Ernest Hemingway” was about to be published. Having seen some of the chapters in advance, we were excited about the new information revealed from the in-depth research. Silvio gave us permission to run a chapter titled “The Winchester Model 21 Shotguns,” which appears following the introduction below.

Ernest Hemingway, the mythic writer and alpha male who began hunting with his father at the age of 2½, drew his literary themes of action, adventure and courage from a lifetime afield in North America, Cuba, Europe and East Africa. As a lifelong hunter and conservationist, he was inspired by the strong example of Theodore Roosevelt, and he much enjoyed teaching newcomers to shoot and hunt. The guns and rifles that Hemingway owned and shot are as interesting as the man himself, and they tell us much about him.

This book, the result of two years of research, is a highly detailed and thoroughly illustrated account of more than two dozen Hemingway guns ranging from a Westley Richards .577 Nitro Express to a Thompson submachine gun, including his beloved Model 12 and 21 Winchesters; Browning, Beretta and Merkel over/unders; a W. & C. Scott & Son pigeon gun; various Colt Woodsman pistols; the Mannlicher-Schoenauers he bought for himself and his wives; and the famous Springfield .30-06 he commissioned from Griffin & Howe in 1930.

The authors have traced the origin, use and, wherever possible, fate of these iconic guns. The book includes nearly a hundred photographs – many rarely seen – and ends with a description of the “CSI”-style investigation that finally identified the gun that Hemingway used on himself on the morning of 2 July 1961. Including brief excerpts from Hemingway’s works, these histories of his guns and rifles will appeal to both shooting enthusiasts and Hemingway aficionados.

The Winchester Model 21 Shotguns

For her 32nd birthday, 8 November 1940, Ernest Hemingway had promised Martha Gellhorn, who became his third wife two weeks later, a shotgun. They were already in their second autumn in Sun Valley, and Hemingway was well into the next stage of his uniquely eventful life. In the long run, Idaho had a greater impact on him than Gellhorn did.

A year earlier, in mid-September 1939, Ernest had packed up his black Buick convertible and left Olive and Larry Nordquist’s L-Bar-T, in the Clark’s Fork Valley of Wyoming. Like Key West in winter, the dude ranch had been his summer and fall refuge through the 1930s, the place where he could write in the mornings and then play – ride, fish, hunt – with his family in the afternoons. (“Play,” however, that infused his writing.) But, along with his marriage to Pauline Pfeiffer, that period was over now and he needed a new sanctuary. Picking up Martha in Billings, Montana, he drove west into Idaho and checked into room 206 in the Sun Valley Lodge. He went not to fish or hunt, but to finish For Whom The Bell Tolls.

Sun Valley, the brainchild of the Union Pacific Railroad’s Averell Harriman, had opened in 1936 as the first ski resort in America. Harriman knew Sun Valley had to be an all-season destination in order to succeed, and he hired fishing and hunting guides, equestrian trainers and even ice-skating coaches in addition to ski instructors. To help spread the word, Harriman’s publicity department invited the influential, famous and connected to Sun Valley, often on the resort’s dime. Hemingway, at the age of 40, was all three.

Hemingway’s first visit turned into a stay of many weeks and changed his life.

Westerners generally did not treat him as a celebrity but judged him on more down-to-earth criteria – could he ride, shoot, drink, treat a lady with respect, tell a good story? – which pleased him. In addition, despite the glamour that would increasingly attach to it, Sun Valley was sheep country, complete with Basque shepherds, which reminded Ernest of the Sierra de Guadarrama, north of Madrid, which he had come to love while covering Spain’s Civil War in 1937 and ?38. And there was world-class hunting and fishing. Hemingway returned to Sun Valley every fall as often as he could, and after the Cuban revolution he bought a home in nearby Ketchum and ran out the balance of his life in Idaho.

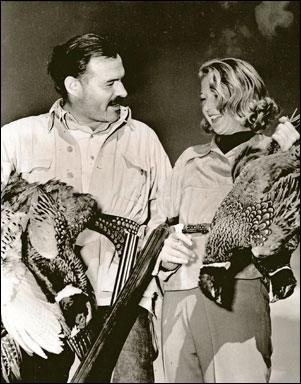

Lloyd Arnold/John F. Kennedy Library

Often rising at dawn to write until late morning, Hemingway might then pack a lunch and go out with the locals who became his close friends. Shooting ducks along Silver Creek, the Big Wood River and in the Hagerman Valley, walking the fields and creek bottoms in the Magic Valley for pheasants and quail, hiking after chukar and Huns in the Picabo Hills, waiting for flights of doves near Timmerman Hill, pounding the sagebrush in Blaine County for grouse, stalking the valley sloughs for snipe – all provided Papa with bird hunting he called the best in the world. In the Sawtooth Mountains there were mule deer and elk, and Hemingway’s story “The Shot” is about an antelope hunt in the Pahsimeroi Valley, north of Ketchum.

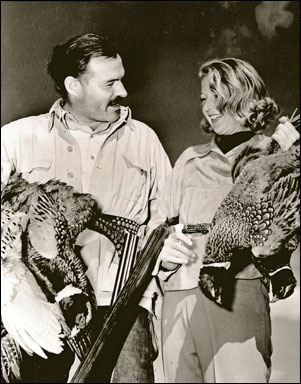

Naturally, Hemingway never was just one of the gang; he formed and led the gang – “the tribe,” as his friends called themselves: Taylor Williams; Lloyd Arnold and his wife Tillie; Clayton Stewart; Pete Hill; Forrest MacMullen; Don Anderson; Win Gray; Bud and Ruth Purdy; Charles Larkin; Tom Gooding; John Powell; Chuck Atkinson; Dr. George Saviers; Clara Spiegel. They were ranchers and professionals and resort staff, locals and transplants, young and middle-aged. Papa’s Hollywood friends – among them Gary and Rocky Cooper, Clarke Gable, Ingrid Bergman, Howard and Slim Hawks – came to Sun Valley to hobnob with him too. There was tennis and riding and fishing and famous parties at Trail Creek Cabin, but guns, shooting and hunting often dominated.

Jump-shooting ducks from a canoe was popular. Hemingway took his turn paddling while another hunter shot from the bow, “the throne”; for safety, the paddler in the stern never shot. This was a lesson hard learned. In November 1939, Gene Van Guilder, the young resort publicist who’d lured Hemingway to Sun Valley, was killed while duck shooting from the bow. Lloyd Arnold was in the stern and another man in the middle. Something went wrong. The canoe rolled violently, the middle gun discharged and Van Guilder was shot in the back. Although Hemingway had known him for only six weeks, Van Guilder’s widow asked him to speak at the interment. Twenty-two years later Papa, also victim of a shotgun, was buried two graves away and the famous eulogy he’d written for Van Guilder was said for him as well: “Best of all he loved the fall . . . .”

Jackrabbits were so plentiful that Idaho paid a bounty of 10¢ per animal. They multiplied wildly and sometimes thousands overran a farm and its crops. Hemingway organized rabbit drives, with himself as the “General” of a small army of guns and beaters, with lunch at the farmhouse and hundreds of rabbits taken. Hemingway often supplied the ammunition and gave the bag to the farmer for the bounty. Such random acts of kindness became a Hemingway tradition in Idaho.

Hemingway enjoyed having women take part in his favorite pastimes, no matter what they initially thought of bullfighting or guns or gamefish. According to Ruth Purdy, Hemingway’s position was, “When we go hunting, you’re going to go hunting,” and he took great pleasure in introducing newcomers to shooting. One of these was his fiancée Martha. She admitted to friends that she would prefer to go riding instead, but she bowed to Ernest’s wishes and set about learning to handle a shotgun. At first it was a balky pump-action .410 – despite its negligible recoil, a notoriously difficult gun to shoot well because of its small shot pattern. Taylor Williams, the resort’s chief guide, saw the problem and substituted a double-barreled 20-gauge from his supply of loaner guest guns. Martha’s performance immediately improved and Ernest promised that as soon as he came into some money he’d buy her one just like it – a Winchester Model 21.

With the publication of For Whom The Bell Tolls, in October 1940, the money began to roll in. Hemingway already had at least one Winchester, the Model 12 pump shotgun he’d acquired more than a decade earlier, and his father Clarence had had a Winchester lever-action shotgun. To a nation for whom the settling of the Wild West was still just a generation or two in the past, the Winchester name was even more familiar and American than Ford or Coca-Cola.

Unlike Ferdinand Mannlicher, John Browning or William Middleditch Scott, Oliver Fisher Winchester was an unlikely gunmaker. Born on a farm in Massachusetts in 1810, he was apprenticed to a carpenter when he was 14 and became a master builder. Later he opened a retail store that sold men’s goods, which led to a fortune in men’s shirts. In 1855 he invested in the Volcanic Arms Company, in Connecticut (founded by Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson, who went on to handgun fame), which with him as president became the New Haven Arms Company in 1857.

Other American firearms pioneers such as Eli Whitney and Eliphalet Remington were skilled machinists; Oliver Winchester’s strengths were promotion, fiscal management and the ability to select talented employees and good products. When the American Civil War erupted, in 1861, Winchester’s company was making a lever-action, 16-shot repeating rifle called the .44 Henry. At first the Union’s Chief of Ordnance refused to buy it – too fragile, he decided, and it required specialized ammunition. That view was not shared by soldiers, who bought Winchester’s rifle and ammunition for themselves. By 1863, the Union and several European governments were also buying, and the company emerged from the war a success. In 1866 Winchester sold the shirt business and re-named New Haven Arms the Winchester Repeating Arms Company. Thereafter all rifles and shotguns, beginning with the Model 1866 and eventually including many designed by John Browning, carried his name. New models and foreign contracts, with particularly large sales to China and Turkey, followed in the 1870s.

When Winchester died, in 1880, his lever-action rifles were – along with Colt’s six-shooter – embedded in the world’s consciousness as American icons, the “guns of the Wild West,” and the business was valued at $3 million.

The company passed to Oliver’s son, William Wirt Winchester, who died within three months of his father. William’s wife Sarah inherited half of the company and an income of $1,000 a day. After losing not only her husband and father-in-law but then also her daughter, Sarah came to believe the family was cursed because of all the deaths caused by Winchester rifles. A medium advised her to build a house for herself and the spirits – and that if construction ever stopped, she would die. In 1884, in what is now San Jose, California, she started adding rooms to a farmhouse. Construction continued around the clock, seven days a week, 365 days a year for the next 38 years. Upon Sarah’s death, in 1922, the house had 160 rooms. Her niece auctioned off the house and employed movers to empty it – eight truckloads a day for six and a half weeks. It is now a National Historic Monument known as the Winchester Mystery House.

After the turn of the 19th Century, Winchester dominated the repeating-shotgun market, with its famous Models 1897 and 1912 pump guns. What Winchester lacked, however, was a double-barreled gun.

By the late 1870s, many of America’s leading gunmakers – Colt and Remington, as well as smaller firms such as Parker Bros., L.C. Smith, Fox and Lefever – were building European-style side-by-side shotguns. Winchester was notably absent from this market. In 1878 or ‘79, the company treasurer, William W. Converse, traveled to England and bought a number of inexpensive Birmingham-built double guns. These sold quickly, although, by most accounts, they were never marked “Winchester.” Given this initial success, in 1880 the company decided to import shotguns from Birmingham that would carry the Winchester name. Ultimately, about 10,000 guns – made by W. & C. Scott & Son, among others – were brought into America.

Legend has it that in 1883 P.G. Sanford, the manager of Winchester’s New York store and office, complained that it was unseemly for a prominent American arms and ammunition manufacturer to sell imported shotguns. The executive team apparently agreed and, on 12 May 1884, sold the remaining stock of English “Winchesters” to the New York firm of John P. Moore’s Sons.

Unseemliness aside, there are two other, more hard-nosed rationales for this decision. The first is that Colt allegedly agreed not to enter the ammunition business if Winchester would stop importing shotguns. (As the Sherman Anti-Trust Act would not be passed until 1890, such collusion was still kosher.) The second explanation seems more likely: President Chester A. Arthur’s Tariff Act of 1883 imposed an ad valorem duty, a value-added tax, of 35 percent on imported shotguns.

It was time to change direction. Within a few years, Winchester began producing single-barrel repeating shotguns – first John Browning’s lever-action Model 1887 and then the legendary pump-action models – at home, and a double-barreled Winchester gun did not emerge for another 40 years.

To many shooters, particularly in America, the Model 21 was worth the wait. Its design was the sum of contributions by at least five Winchester designers –T.C. Johnson, Edwin Pugsley, George Lewis, Louis Stiennon and Frank F. Burton – over more than a decade, and Winchester would boast that the gun’s model name came from the “21 special features incorporated in the design.”

American and British makers have never quite agreed on the best configuration for a side-by-side double-barreled gun. Best-grade British guns typically have double triggers, slender “splinter”-style stock forends under their barrels, and detachable sidelock actions. American doubles, on the other hand, favor single triggers and larger, wrap-around “beavertail” forends, and are built on less-complex, but arguably stronger, solid-frame boxlock actions.

Nonetheless, the standard boxlock action, patented on behalf of gunmaker Westley Richards in 1875, is a British design, which may explain why Winchester chose to develop its own boxlock mechanism and enough other features sufficiently innovative to earn nine patents for the Model 21.

All firearms are subject to enormous forces at the instant a cartridge is detonated; break-action guns, hinged in the middle, want to open up under these pressures, which makes their locking systems critically important. Not only must they resist this instantaneous shock, they also have to absorb many thousands of rounds before the hinge shows any loosening due to wear. In addition to a sliding underbolt, British and European double guns often have a short extension from the barrels that fits (when the gun is closed) into a slot in the action body and then is pinned by a sliding crossbolt or the like. Winchester’s Model 21 had no such extra fastener. Its great strength came from a longer action bar, which reduced the leverage of the detonation, and from unusually stout construction. The gun’s barrels were made from Winchester Proof Steel, a patented chrome-molybdenum alloy specially heat-treated to a tensile strength of more than 60 tons per square inch –double the usual. Each barrel began as a solid forged rod and, after machining, the two resultant tubes were fitted to each other across a long, integral vertical dovetail, which was then silver-soldered. While English-style guns have handmade V springs inside, the M21’s hammers and ejectors were powered by machine-wound coil springs. The Model 21 also got an improved safety catch and its own reliable selective single-trigger mechanism – one trigger that can be set to fire either barrel first. (Double triggers were an available, extra-cost option.)

When it was officially introduced, in 1931, Winchester described its new top-of-the-line shotgun as “equal in design and quality to any double model anywhere, and of superior design and craftsmanship.” In reality, the Model 21 was overbuilt and heavy. The United Kingdom and Europe had, and still have, national proof houses, which test-fire and certify each individual gun made in that country to a certain standard of ammunition. Manufacturers build their guns to those standards and no more, and mark each gun to that effect; the shooter over-loads it to his or her peril. America has never had a proof house, and gunmakers must err on the side of caution to ensure that some unusual, nonstandard ammunition doesn’t blow up their products. Using “Violent Proof” loads with powder charges 50-percent greater than normal, Winchester tested its Model 21 against four US-made competitors. The others failed after firing anywhere from 56 to 305 such cartridges; the M21 was still in good working order after digesting 2,000 of them. The Model 21 remains one of the strongest double guns ever made.

In addition, Winchester produced the Model 21 to unusually exacting specifications; parts were said to be interchangeable from one gun to another, which is not true still today in many double guns, which require final hand-fitting. This was an impressive feat of industrialization in a world where computer-controlled machining was not even imagined yet.

The Model 21 debuted as a 12-gauge for $59.50, equivalent to about $765 in 2010. Given that the Great Depression had just started, this qualified as a master stroke of poor timing. Winchester had gone into receivership in 1930 and was sold to the Western Cartridge Company, owned by Franklin W. Olin. His son, John M. Olin, a hunter and shooter who became a force in American business, eventually took over Winchester-Western (as the company was known after 1935) and personally “adopted” the Model 21. Thanks to Olin, the 21 eventually achieved fame as the double gun for the affluent American shooter who demanded durability above all else. Model 21s differ in the quality of wood and the degree of engraving, but never by quality of construction or materials.

In its lifetime, the Model 21 was made in more than 27 grades ranging from plain field guns to incredibly ornate “Grand Royal” showpieces. (Seven of these were planned; only three were ever completed.) From 1930 to ’40, the price of a standard M21 approximately doubled. But when production resumed after the Second World War, the price jumped to $185 in 1946 ($2,100 today) and thereafter costs rose steadily. With sales averaging fewer than a thousand a year, the Model 21 was trapped in an unprofitable limbo somewhere between low-price mass-production items and high-cost bespoke guns. In 1959 Winchester decided to offer the 21 on a made-to-order basis only and charge accordingly. By then, approximately 30,000 M21s had been made; by the time the Winchester Custom Shop closed, in 1993, a further thousand or so had been produced. In 1995 a small private enterprise called the Connecticut Shotgun Manufacturing Company bought the remaining Model 21 parts and the rights to make the gun again.

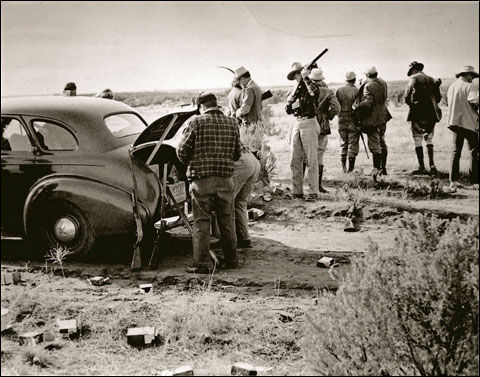

Brad Stanley/John Cymbal: Driven

Book 8 of Abercrombie & Fitch’s ledgers records the sale to Ernest Hemingway of Model 21 No. 15593 on 18 December 1940 for $117.30. It was a Skeet-grade 20-gauge with 26-inch barrels, choked Skeet #1 and Skeet #2. It had a full pistol grip, a beavertail forend and the standard single selective trigger, and it weighed 6 pounds 11 ounces. The stock had a length of pull – the distance from the trigger to the center of the buttplate – of 143/8 inches and drops (measured from the extended line of the barrels to the top of the stock, fore and aft) of 1½ and 23/16 inches. It would have had the standard thin, hard-rubber buttplate.

Today No. 15593 has a soft, leather-covered recoil pad and its stock has been cut down to 13½ inches.

Earlier in 1940, however, Hemingway bought another 20-gauge Model 21, serial number 14267. Winchester’s production records for No. 14267 are confusing. The original sheet – now part of the vast Winchester collection at the Cody Firearms Museum in Wyoming – was written over in some places and scratched out in others. Warren Newman, the Cody firearms curator, wrote in an e-mail, “As best I can interpret [the records], this firearm was originally manufactured on 2 January 1940. It must have come back to the factory on 10 December 1940, and gone out again on 25 January 1941.

“Hemingway’s name is not in the records. The only contact data is ‘Cia Piera Toras, Van Nusston, S.A.,’ but we are unable to make any real sense of it.”

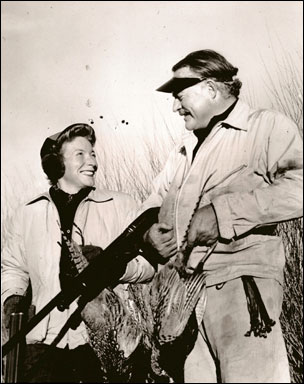

John F. Kennedy Library

The gun does not appear in Abercrombie & Fitch’s books, so it was bought elsewhere – perhaps from another dealer or a private individual, perhaps even from the Sun Valley Resort. (Was it the very gun Martha had done well with, loaned by Taylor Williams?) “Cia Piera Toras, Van Nusston, S.A.” is a mystery as well. No. 14267 is also a Skeet-grade gun with a single selective trigger and a beavertail forend. Today it has 28-inch barrels choked Full and Full and its length of pull is only 12¾ inches. The gun has a silver button set into the end of its grip on which are engraved the initials M.G.H.

Lloyd Arnold wrote that in November 1940 (a month before Hemingway bought No. 15593 from A&F) he saw in Ernest’s gun rack at the Sun Valley Lodge a new Model 21 Winchester in 20 gauge – “his promised gift to Marty on her birthday” – with “an extra set of barrels for long-range work.” 1 And M.G.H. is Martha Gellhorn Hemingway. Martha’s birthday present is surely M21 No. 14267. It could have been sent back to New Haven in the following month to have the engraved silver escutcheon added or the stock shortened.

In the 67 years between the time Martha received the gun and it was sold to its present owner by James D. Julia Auctioneers, in October 2007, one set of barrels – the more open-choked barrels, suitable for upland birds in Idaho – has disappeared, leaving only the Full & Full set on the gun. Photos of long-legged Martha standing next to her six-foot husband indicate she was a tall woman, and at least by modern standards 12¾ inches seems short for her – but not for the next Mrs. Hemingway, a petite 5’2”, who “inherited” it.

Ernest evidently bought Model 21 No. 15593 from Abercrombie & Fitch shortly after he’d gotten his wife’s gun, No. 14267. If in fact he’d shipped her birthday gun to Winchester a week earlier, as the record suggests, No. 15593 could have been a replacement for her to use while hers was being modified. Since No. 14267 evidently was not shipped out again by Winchester until January 1941, she would otherwise have missed parts of two hunting seasons.

No. 15593 does not appear to have been Ernest’s gun; except for his early 16-bore Browning A-5, his shotguns seem to have all been 12-gauges, and every side-by-side double gun in his hands in photographs looks to be his English W. & C. Scott.

Ernest’s and Martha’s marriage lasted five years. Next up, after Word War II, was Mary Welsh, another journalist, who became the fourth and final Mrs. Ernest Hemingway on 14 March 1946. Her indoctrination into shooting had begun the previous summer, in Cuba, when she wrote the lines at the top of this chapter. Gigi – Ernest’s youngest son, Gregory, just turned 17 – offered to teach her to handle the Model 21: “bead on target, head down, stock firm at shoulder.” He had her shoot at a cardboard box at different ranges, to show her how the shot pattern spread with distance; then came the daily flight of negritos, small black birds that fed in the fields and returned to their roosts in the trees of Havana each evening. “Move with them and shoot,” Gigi said, and demonstrated. With each shot a bird fell, some so far off that Mary thought they might have had heart attacks. When it was her turn, Mary fired and reloaded and fired again until the cartridges were gone – one bird down. Back at the house, Papa asked how she’d done. “Okay,” Gigi replied. “Okay for a first go.” 2

John F. Kennedy Library

Over time the two Model 21s, all but identical, became known in the family as “Mary’s guns,” and Mary herself became, in her husband’s pronouncement, a “brilliant but erratic shot.” She was always more comfortable shooting birds than four-legged game, and she shot the Model 21s far more than she did her Mannlicher-Schoenauer rifle. (After Ernest’s death, she once ran off some unwelcome visitors to the Idaho house by firing one of her 21s at their car.) Mary continued to hunt after Ernest’s death, sometimes with her friend Clara Spiegel in Idaho. She returned to East Africa in 1962 to go on safari with her stepson Patrick, and she hunted with Sports Afield columnist and trapshooting great Jimmy Robinson at his waterfowl lodge near Winnipeg, and with a young man from Southern California named Bruce Tebbe.

Tebbe was a friend of Denne Bart Petitclerc, the reporter-turned-scriptwriter who became a Hemingway friend and moved from California to Sun Valley. Petitclerc in turn introduced Tebbe to Mary Hemingway after Ernest’s death, and the two of them often hunted together with the Model 21s. The 12th clause in the Last Will and Testament of Mary Hemingway, dated 26 October 1979, directed that when she died her two 20-gauge Model 21 Winchesters would go to Bruce Tebbe. He sold them in the late 1980s – to his regret, he said – and eventually, in October 2007, the two guns appeared in the same James D. Julia auction that offered Hemingway’s Woodsman pistol No. 128866-S. The same bidder, a Michigan sportsman and Hemingway aficionado, bought all three.

ISBN: 978-0-89272-720-9

Hardcover, 156 pages, 98 sepia-tone photos, 8.5” x 11”, $40.

Available in October 2010 at www.shootingsportsman.com or by calling 800-685-7962.

Irwin Greenstein is Publisher of Shotgun Life. Please send your comments to letters@shotgunlife.com.

Comments