Remembering Michael

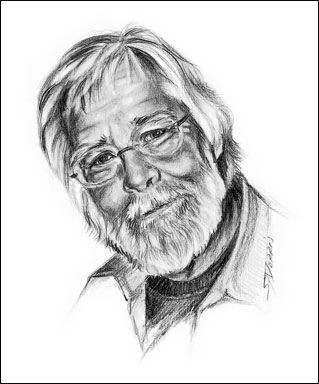

Michael McIntosh, one of America’s foremost shotgun writers died on Saturday, August 14, 2010, at his home in Iowa. He was 66 years old.

Michael McIntosh, one of America’s foremost shotgun writers died on Saturday, August 14, 2010, at his home in Iowa. He was 66 years old.

Other people called him Mike, but I never did. To me, he was always Michael – and if a finer friend than Michael McIntosh ever existed, I have yet to meet him.

For a quarter of a century, our lives intertwined in ways that were sporadic and unpredictable, at times almost eccentric, but always influential. To say that Michael McIntosh changed my life is to understate the case by several degrees.

In fact, Michael’s influence began before I ever met him. In 1985, in a bookstore in Toronto, I found a slim little volume called The Best Shotguns Ever Made in America.

At the time, my interest in shotguns, shooting, and hunting in general had just reawakened after almost a decade of gin-soaked existential angst in which I read more Ibsen than O’Connor, more Malcolm Lowry than Robert Ruark, and I was sorely in need of the sweet smell of gunpowder.

Michael’s book, essentially a collection of articles he had written in the 1970s while editing the Missouri conservation department magazine, had the desired effect. A few months later, I simultaneously discovered, on a magazine rack, both Sporting Classics and Gray’s Sporting Journal. Michael was the shotgun columnist for Sporting Classics, and one of the first things I did after beginning to write for them myself was send Michael a letter.

There began the aforementioned quarter-century-long friendship in which we talked, wrote, advised, consulted, occasionally edited, traded forewords for each others’ books, and generally trod parallel if meandering paths through a world of fine whisky, finer guns, and an exploration of the finer feelings that accompany any wingshooter who truly appreciates that gift from the gods.

* * *

Michael McIntosh was born in the Midwest and grew up, as I was given to understand, in Iowa and Missouri, and when we met he lived on a farm near Camdenton. He had just quit the world of paid employment for the uncertain life of a freelance writer. At various times, I read that he was an Elizabethan scholar and had taught Shakespeare at a college, but it was not something we ever discussed.

Although he certainly retained a deep interest in literature, and an even deeper one in history, his great love was shotguns and he wrote about them almost exclusively. And, to be blunt, no one in the latter part of the 20th century wrote about them so eloquently and with such passion.

Although I did not have the knowledge of doubles that Michael had, I think he detected in me a kindred spirit, and that formed the basis for our friendship.

It was Michael McIntosh’s goal in life to take his love of Purdeys and Parkers, Holland & Hollands and Foxes, and awaken that same passion in others. The extent to which he succeeded is shown by the renaissance in double guns of all kinds that began in the early 1980s, flowered throughout the ’90s, and continues to this day.

This renewed interest in one of the great classical artifacts of shooting was not due entirely to Michael’s influence. No one – least of all Michael – would suggest that. But unquestionably, no writer did as much for gunmakers and the gun trade as he did.

I suspect that Michael’s closest friend was David Trevallion, the ex-Purdey gunmaker who now lives in Maine and with whom Michael collaborated, for many years, on a column in Shooting Sportsman called “Technicana.” The column explored the arcane nooks and crannies of gunmaking and gun design, from different types of ejectors and how they work, to why screws (pins, to the English, or nails, to some particular English makers) are made and regulated, to the origins of classical scroll engraving.

Michael McIntosh wrote about shotguns the way Tolstoy wrote about beautiful women, with a deep interest and admiration for every tiny aspect of their being, even their faults and vices. Had he been given the choice of being transported back in time to attend the first performance of Macbeth in the company of Shakespeare himself, or working in the Boss & Co. shop at 73 St. James’s Street in 1905, with John Robertson at the next bench, I am quite sure he would have chosen the latter.

* * *

In 1989, Michael published his second major book, Best Guns, a treatise on fine doubles around the world that sold out, was reprinted, and has remained in print for more than 20 years. In the course of researching the British section (the tone of which is reflected by its title, “Britannia Rules”) Michael uncovered vast amounts of information about the simultaneous development of big-bore rifles.

Michael McIntosh was always at pains to disclaim any real interest in rifles. He had, he once told me, a Mauser ‘98 kicking around somewhere, but he had not shot it in many years and did not even know where it was.

The instant success of Best Guns, however, prompted the publisher, Countrysport Press, to demand that Michael take the rifle-related material and turn it into a book. This he did – The Big-Bore Rifle – and it was only natural that, since I was then the rifle columnist for Sporting Classics, that I write the foreword.

With that began our long, sporadic collaboration on books, which Michael began by introducing me to his publisher and then continued by encouraging me in every subsequent writing project.

I do not believe Michael McIntosh had a jealous, envious, or egotistical bone in his body. If he did, I never saw any evidence of it. No matter what I attempted, even if it encroached a little on his areas of expertise, he was invariably supportive and helped me in any way he could. I returned the favor, I hope, with as much grace.

When it came to authors we admired, our paths diverged slightly. He was a devotee of William Faulkner, whereas I favored Ernest Hemingway. It was a fault for which we forgave each other. We did share a great admiration for Robert Ruark – somewhat strange in Michael, since he was not a big-game hunter. Perhaps it was Ruark’s ultimately tragic pas de deux with the bottle that gave Michael a fellow-feeling for him, since he was as fond of the cup as anyone. One could not call it Ruark’s battle with alcohol, since he put up no apparent resistance. At any rate, Michael set out to do what he could to help resurrect Ruark’s fading reputation.

In 1991, he published an anthology called Robert Ruark’s Africa, a collection of magazine articles from the 1950s. Not only did it help resurrect Ruark, it sparked the publication of further volumes of “lost classics” by Ruark (and ultimately by others, like Jack O’Connor). Although Michael never did get to Africa, he never seemed to regret it; possibly, he saw it in his imagination and was privately grateful that the reality never intruded upon his vision of the Africa that was.

While Michael was specializing first in American doubles, and later in English guns, I was venturing to Spain. Several visits to the Basque gunmakers in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s resulted in a book, Spanish Best, which owed a great deal to him. First, he encouraged me to write the book; then, he found me a publisher, and finally, he edited the manuscript. The book went through two printings (or was it three?) and in 2002 I embarked on a second, expanded edition. Again, Michael McIntosh edited the manuscript and also wrote the foreword.

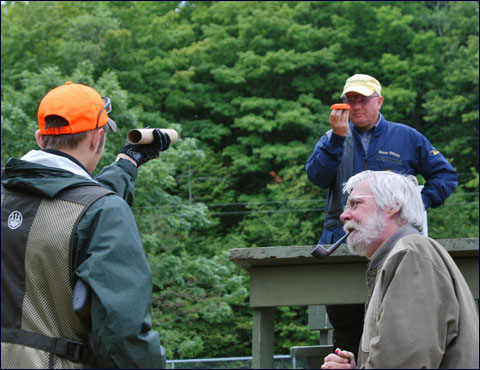

That summer, we met in Traverse City, Michigan, where he was teaching at Bryan Bilinski’s shooting school, and we had dinner together.

A dinner in a chain steakhouse is hardly remarkable, yet it remains vividly in my memory, partly because, in spite of our long acquaintance, Michael and I saw each other seldom. Although we talked about it, we never once went hunting together, or even shot clays on a range. In 25 years, I suspect we met face to face no more than eight or nine times, and yet I remember every single encounter, and I also remember that every one had its own significance.

At the 1991 Safari Club convention (one of the very few he ever attended) we shared a cheap hotel room to save money, consumed more whisky than we should have every single night, and embarked on one memorable pub crawl through a down-at-heel part of Reno. Hangovers aside, I particularly remember him seeking me out at the convention one morning and leading me over to a dealer in fine guns who had a James Woodward 28-bore over/under for sale (asking price: $75,000). Together we handled the Woodward (gently, carefully, under the watchful eye of the dealer) and in that moment, more than any other, my amour with English guns began.

Then there was the Gray’s affair. Well, not really an affair. In 1993, David Foster offered me the job of shooting editor of Gray’s, which I accepted. I called Michael to tell him and he was effusive in his congratulations.

A few weeks later, I received a call from Holland & Holland, inviting me to London for two weeks as their guest, all expenses paid, to see their new Chanel-financed operation and do some shooting. This was the beginning of my own long association with Holland & Holland, which grew into enduring friendships with several of its people.

It was only later that I found that Holland’s extended the invitation on the recommendation of Michael McIntosh, who was on close terms with them, and told them it would be to their benefit to get to know me.

And it was much later still that I learned that Michael had known the Gray’s job was about to be created, and had really wanted it himself. The generosity of that gesture in the face of his own disappointment defines, for me, the character of Michael McIntosh.

* * *

Michael was married many times, divorced almost as many, and moved around frequently. He never initiated a phone call, rarely returned them, and eschewed e-mail as he avoided cheap whisky.

By 2004, he was living in the Black Hills of South Dakota, and had mysteriously dropped from sight. None of his editors seemed to know where he was. In Sturgis on some business with Dakota Arms, I took an afternoon and drove down to try to find his last known address, and if possible, Michael himself. I found the house, locked, shuttered, and seemingly abandoned. His neighbors in the upscale and quite delightful woods where he lived had not seen him for more than a month.

I returned to Sturgis more worried than ever. It was only after I got home that I was informed that he was having serious health difficulties and had actually checked into a clinic, ostensibly for any number of reasons, but in reality, to try to stop drinking.

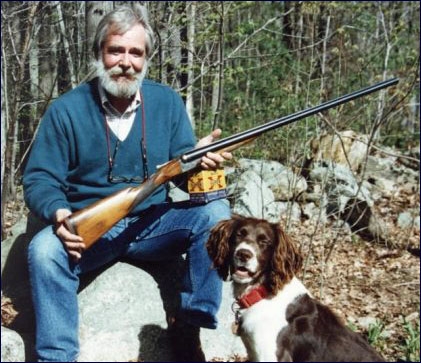

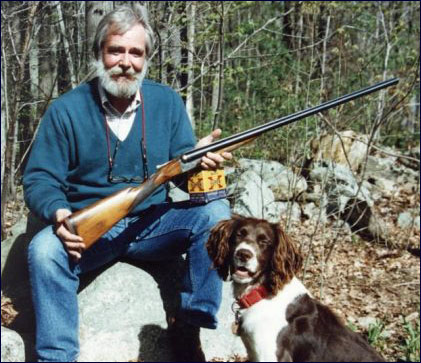

(Photo courtesy of Chris Chantland/Fieldsport).

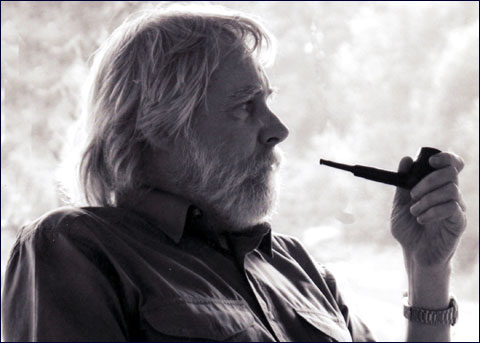

It is no secret how much Michael McIntosh loved whisky, and without going into detail, he may not have been in the Ruark-Lowry class when it came to draining the last drop, but he wasn’t far off. The miracle was that he survived those two legendary drinkers as long as he did.

One of the very few phone calls I ever received from Michael, however, was made after that abortive attempt to find him. He called to tell me he had moved back to Iowa, and to thank me for the effort.

By that time, he was having health problems of all kinds. His knees were bad – the result of some genetic ailment that afflicted his ancestors, he told me; his eyes were so bad at times he could not write; he resigned from several of his regular magazine columns, sometimes formally, sometimes by simply not submitting any more material. When writer and editors gathered, the most common question was, “Have you heard anything from McIntosh?”

My last contact with him came in 2008 when I was writing a book on English guns – Vintage British Shotguns – and I insisted, over the objections of the publisher, that Michael edit it and write the foreword.

He was then a renowned author in our own little world of guns and shooting, with about 10 books in print, several more contracted for, and was Countrysport’s (later Down East’s) best-selling author. But he was behind on some of his contracts (one book manuscript was, I was told, 10 years overdue!) and they had no faith that he would complete the assignment on time.

Being at that time Down East’s second-best-selling author, I stood my ground. Michael, I said, knew more about the subject than anyone else in the country. If he gave me his word, I said, he would deliver.

And, deliver he did. Working with Michael that one last time was delightful. We talked daily and discussed details of Purdey locks and Woodward hammers. He changed a word here and a word there, suggested some additions, cautioned against some of my more extreme opinions, and then wrote a warm and generous foreword.

In his later years, Michael had divested himself of most of the guns he had written about, as his tastes became more focused and refined and his ability to spend long hours shooting became more restricted. At one time, he owned one of almost everything, although the most notable were an AYA No. 2 and an Arrieta 28-gauge, and later a John Wilkes sidelock that his friend David Trevallion restocked for him.

Michael was a little reticent in print about what guns he shot, presumably not wanting to slight anyone, but as he was editing my book he confided that what little shooting he was now able to do, he did with a Purdey hammer gun.

He once wrote, memorably, that “God the Father shoots a Purdey hammer gun” and I asked how he knew that. He just smiled.

Now, I expect that Michael McIntosh knows first-hand if that is, in fact, true. For my part, I just took his word for it. It was the kind of thing Michael would know.

Terry Wieland is Shooting Editor of Gray’s Sporting Journal, a columnist for Rifle, Handloader, and Safari Times, and author of several books on rifles, shotguns, and big-game hunting. Wieland’s latest best seller, Dangerous-Game Rifles, was published in 2006, and an expanded second edition was published in 2009. Terry’s web site is located at www.terrywieland.com.

Terry Wieland is Shooting Editor of Gray’s Sporting Journal, a columnist for Rifle, Handloader, and Safari Times, and author of several books on rifles, shotguns, and big-game hunting. Wieland’s latest best seller, Dangerous-Game Rifles, was published in 2006, and an expanded second edition was published in 2009.

Terry Wieland, Excellent artical on “Our Young Friend Michael” I think he would have enjoyed reading it.!!!!!!Maybe he has already !!!DT.

Terry, Very generous and wonderful article and general tribute to Michael. Love both his writing and yours. In fact traced your steps to Eibar after working for the Catalonian Fire Fighters and bought 3 Bespoken Grullas. Was a Fox devotee long before Michael, but sure enjoyed hearing his thoughts on the old ones and the new ones from New Britian, Ct. a few miles from where I grew up. I bought a bespoken Fox 28 gauge after hearing his rave reports on them just like being inspired to investigate the Spanish Bests that you laid out. I sure don’t know what I like more now the Foxes (4) 3 old one new or the Grullas. One thing for sure as I carry either of them I sure hear you both talking about them.

I just learned of Michael’s death. I tried now and then over the years to contact him without success. When he was a young professor at Missouri Western College in St. Joe, He, another professor, Karl Klose, and my concrete finisher friend, Russell Leslie who never got past sixth grade comprised our hunting foursome. In those days northwest Missouri was a quail hunter’s paradise and we were afield every weekend of the season. I had hunting permission galore due to the nature of my job. We hunted over two labs I had that made a great team for non-pointers. Eventually Michael got a Brittany pointer. Our team also did a lot of dove hunting and I had fantastic spots around Squaw Creek refuge for snows and blues. Michael always joined in but I know his preference was for upland game. Most of the time he shot a Parker 20 gauge double. I was shooting an AYA Matador and our friend Russell had an assortment of L C Smiths and old Parkers. Some were damascus barreled which he insisted on shooting with modern loads even for geese. In 1972 I took a job in Carroll, IA right in the middle of fantastic pheasant territory and quickly obtained hunting permission on many farms. Two years running my three Missouri hunting partners came to our house for the weekend pheasant opener. Then I moved on to Wisconsin and lost touch. I recently looked up old Russell in Union Star, MO and just now learned of Michael’s death and two days ago discovered that Karl died last week in PA where he was professor emeritus at Susquehanna University. I still go down to Missouri bird hunting, still with the old Matador, but now with a younger generation of hunting partners.

Thank you for your memories of Michael