A Guide to California’s Triple-Threat Quail

The Golden State may not have a reputation as a top destination for hunters, but it’s home to half of the quail species found in the U.S.

If you happened to visit California’s wild lands last spring, you may have noticed an unusual abundance of wildflowers, a deeper-than-normal snow pack or swarms of insects.

To quail hunters, all of these signs mean one thing: improved prospects for good quail hunting. That’s because annual quail reproduction and recruitment are inextricably linked to the amount and timing of seasonal precipitation, which jumpstarts the food chain.

This generally translates into a more-is-better equation, and California hunters are truly blessed when it comes to quail-hunting opportunity. Home to half of the six species of quail found in the U.S., it is the only state that harbors California (valley) Quail, Gambel’s Quail and – my personal favorite, Mountain Quail – in abundance. According to California Department of Fish and Game biologists, every county in the state has at least one of these species. If you know where to look, there are a few areas with suitable overlapping habitat where you can find all three species and complete a “California Slam” in just a day or two of hunting.

Depending on the precipitation, quail numbers can fluctuate dramatically from year to year. Boom-and-bust cycles are common. This is reflected in the annual hunter harvest of quail of all species, which varies from some 500,000 to nearly 800,000 birds. Hunter-success surveys reveal that the average hunter spends five or six days in the field each season in pursuit of these feathered buzz bombs. If you aspire to be one of them, here’s what you need to know in order to bag each species of quail.

Valley Quail

Valley (California) Quail are the most numerous and widely distributed species of quail in the state. Top-producing counties include Kern, San Luis Obispo, Monterey, Tulare, San Bernardino, Santa Barbara, Shasta, Tuolomne, Fresno and Los Angeles, but these are not the only places you can find Valley Quail. Harvest statistics are partly a reflection of where the greatest hunting pressure occurs. Valley Quail can actually be found in suitable habitat just about anywhere in the state outside of the southeastern desert region and below elevations of about 5,000 feet.

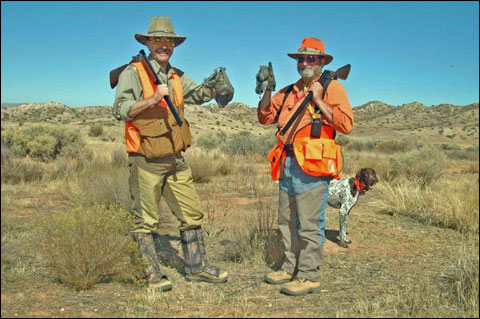

The author (left) and hunting pal, John Whitworth display Valley Quail taken from a classic California habitat of a semi-open area of rolling hills and valleys.

The author (left) and hunting pal, John Whitworth display Valley Quail taken from a classic California habitat of a semi-open area of rolling hills and valleys.While a detailed description of every part of the state hosting Valley Quail could easily fill a book, some general rules apply. First, take a clue from their name. Valley Quail are most often found in areas dominated by rolling foothills and valleys. They seldom stray far from surface water. They prefer weedy, open country and tend to avoid dense chaparral and forests. Think about areas with mixed grassland and brush – especially the early sucessional habitat that follow wildfires – and you’ll be on the right path.

Even though they prefer semi-open areas, they still need sufficient nearby cover to roost in and escape predators. Coveys leave the roost to begin feeding, often towards water, at the first light of day. They may wait much longer if the weather is cold. They may also fly to water immediately in the morning, but more often than not, they’ll feed for an hour or two first. If the area is already lush and green from early rains, they may not go to water at all. After loafing away the midday hours in cover, they resume feeding a few hours before dark if they’re not disturbed. These habits make early morning and late afternoon hours the prime time to locate birds on the move.

Keep an eye out for tracks while you’re covering country. Tracks can give you an idea of the size of coveys and their general direction of travel. Early in the season, before the birds have wised up to hunters, you can locate coveys by listening for their distinctive “Chi-ca-go” assembly calls or by using manufactured calls to imitate the sound. At times, I’ve had as many as five distinct coveys respond to a call simultaneously, with the sentinel roosters sounding madder by the minute as they tried to outdo one another and call the gals back into their covey.

Also watch for Cooper’s hawks while hunting. They are dedicated quail predators, and if any are in the area, it’s a safe bet that the quail won’t stray far from thick cover. You can use this fact to your advantage if you find that you’re hunting “educated” birds that flush far out of range or continually run ahead of you. A call that imitates the scream of a hawk will often freeze them in place.

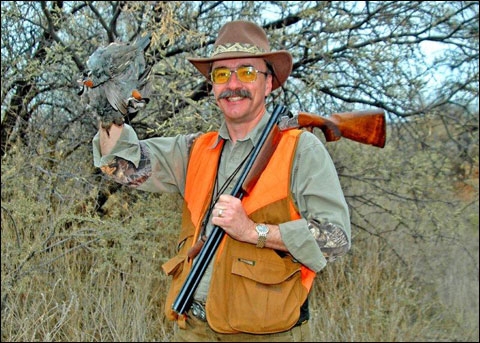

A 20-gauge shotgun, like the author’s Beretta Silver Pigeon, is the classic quail-hunting gun.

A 20-gauge shotgun, like the author’s Beretta Silver Pigeon, is the classic quail-hunting gun.Valley Quail will often hold extremely tight, especially after a covey has flushed. Individual birds will frequently let you walk past and flush behind you. In one memorable instance, I stopped chasing a covey long enough for our small party of hunters and dogs to rest a bit and drink some water. A full ten minutes later, with three hunters and two dogs milling around, we were astonished when three quail flushed from a small bush, practically from under our collective feet.

Be sure to work any gullies or small washes. Valley Quail seem uncommonly fond of these spots, especially if there’s a trickle of water in the bottom. “Running the gullies” is a time-honored trick when quail are difficult to find. Apart from this tactic, it’s generally best to hunt Valley Quail from above or, better yet, station several hunters at varying elevations as you work across the face of a hill or side of a canyon. Valley Quail would much rather run uphill than downhill, and if you spend all your time chasing the uphill runners, your odds of catching them are slim. They flush downhill if you are hunting them from above and will flush uphill if you are hunting them from below. Even when they flush downhill, they will often run back uphill at the first opportunity, typically to a ridge offering multiple escape routes on the other side.

While any shotgun will suffice, a light, 20-gauge double gun stoked with size 7½ shot, choked improved cylinder and modified, is classic Valley Quail medicine. You may want to carry extra choke tubes with you so you can adjust the shot pattern depending on whether the birds are flushing near or far.

Mountain Quail

As their name implies, Mountain Quail – the largest species of quail in North America – are at home in the high country. They generally inhabit areas above 5,000 feet in elevation, moving higher in summer and dropping down below snow line in winter. Wherever you find them, they can be a very tough bird to hunt due to the rugged country they inhabit. If the elevation and vertical landscape doesn’t slow you down, their habit of fleeing into utterly impenetrable brush can thwart your best-laid hunting plans. They’re also highly adept at putting trees between themselves and a shot pattern. In my book, these traits make them one of the most challenging – and rewarding – birds to hunt in all of North America.

A hunting pal of mine summed it up succinctly when he said, “If Valley Quail behave like gentlemen, Mountain Quail are career criminals.”

Mountain Quail are the largest and most handsome species of quail in North America, as illustrated by this mounted pair from the author’s collection.

Mountain Quail are the largest and most handsome species of quail in North America, as illustrated by this mounted pair from the author’s collection.The greatest annual harvest of Mountain Quail typically occurs in Fresno, Siskiyou, Kern, Trinity, Shasta, Tulare, Tuolumne, San Bernardino, Humboldt, Plumas, El Dorado, Lassen and Los Angeles counties.

Finding Mountain Quail is usually a matter of finding the right elevation. Birds that live in the higher elevations migrate lower with the first snowfall. Some may move as much as 20 miles. I’ve found them as low as 3,000 feet in country that looked more like parched desert than the high mountains. In that instance, the birds were concentrated in gullies that held a trickle of water.

The good news is that Mountain Quail tend to use the same areas year after year – at the same time of year – near reliable sources of water. Birds that live in lower elevations in places like the coast range, where snowfall is a rare occurrence, may not migrate at all. It pays to make careful note of locations where you’ve found birds in the past and revisit those areas, assuming they’re not under snow. As a rule of thumb, start searching at an elevation of about 5,000 feet and work up or down as conditions dictate.

While the birds generally abhor open spaces and don’t like to cross roads when they’re pressured, you can often locate coveys by watching for tracks crossing dirt roads or trails. A little pre-season scouting can greatly increase your odds of locating coveys before the season opens.

When hunting with dogs, start by working the bottoms of valleys or stream beds early in the morning while downhill air currents carry scent to the dogs. Birds generally water after their morning feeding, and this can be a good time to spot coveys on the move. Be prepared for the birds to flush uphill and carefully observe where they go. Once flushed, scattered singles and doubles often hold very tight. In the afternoons, when air currents are reversed, try to work areas above suspected covey locations.

If you’re patient, flushed birds will sometimes circle and return to the area they flushed from. On one memorable occasion, I spotted a sizeable covey while driving along a dirt road. I bailed out of the truck and the birds led me on a merry two-hour chase down the side of a mountain until they eventually eluded me. I made the long, tiring hike back up the mountain only to find the entire covey calmly pecking at the gravel around my vehicle.

At times, Mountain Quail can be called successfully by imitating their assembly call with a mouth call. This tactic can be a very effective on scattered birds. The birds may not answer the call, but if you’re patient and still, they may walk right into your location.

Wherever you hunt them, use an open choke and a fast-handling shotgun. Shots are likely to be fast and fleeting. A good bird dog is a must to avoid losing wounded birds in the thick escape cover that typifies a lot of Mountain Quail habitat.

Gambel’s Quail

Gambel’s Quail are true creatures of the desert. They have evolved and adapted to survive in the harsh, arid southeastern region of the state. The bulk of the annual harvest occurs in Imperial, San Bernardino, Kern, Riverside, San Diego and Inyo counties.

While these birds can get by on less water than other quail, reproduction depends heavily on seasonal rainfall and subsequent growth of annual plants and legumes. In years of good precipitation, coveys can number as many as 40 birds. In an extreme high-cycle year, you may occasionally discover concentrations of several hundred birds in a relatively small area. Periods of prolonged drought can, however, make it difficult to find a feather, let alone a covey, in that same spot.

By the time hunting season rolls around, birds are often concentrated near sources of water, such as springs and guzzlers. Places where water and cover come together, such as washes or the base of hills, are prime spots to begin your search.

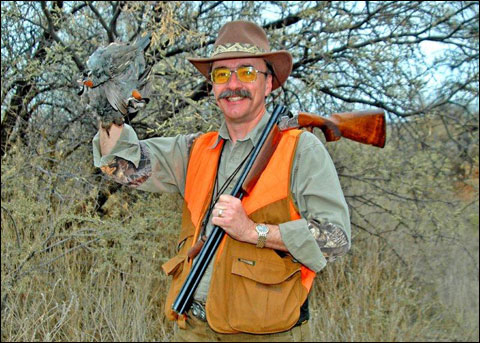

Washes containing both cover and water are hotspots for Gambel’s Quail like these taken by the author.

Washes containing both cover and water are hotspots for Gambel’s Quail like these taken by the author.If you’re going to pursue these desert-dwellers, you may want to leave your dog at home. Dogs generally don’t fare well in close encounters with cacti or Mojave green rattlesnakes. For that matter, neither will you. That’s why I heartily recommend wearing sturdy, puncture-resistant boots and snake chaps. If you do decide to hunt with dogs, it’s a good idea to put protective booties on their feet, carry tweezers to remove cactus spines and make sure they’ve had recent snake-avoidance training.

Be prepared to log a lot of mileage on those boots, as well. More than any other quail in California, Gambel’s Quail purely love to run at the first hint of danger. Simply walking after them is a losing proposition. Say, for example, you spot a concentration of tracks and hear rustling in cover ahead of you. If you walk after the birds at a normal hunting pace, you will likely never see a bird. They’re that fast.

So what’s a hunter to do? There are a few tricks that can tilt the odds in your favor. The first is to – very carefully, and with the safety engaged – trot after them. You won’t find this tactic endorsed in any hunter safety class, but it’s often the only way to get within range. The second trick is to use a call that imitates the screech of a hawk. This may or may not freeze the birds long enough for you to close the range. You may also divide your forces, sending hunters to approach a covey from opposite directions. Again, safety is the paramount concern if you employ this tactic. Take great care to be aware of each other’s location and fields of fire, and take only safe shots.

A friend and I employed this tactic once on a large covey that refused to stop running. He approached from one side of a hill while I approached from the other. Rounding a corner, I was startled when the 40-bird covey flushed directly at me from close range. I could have bagged as many birds by swinging the shotgun as a bat as I did by using the business end, but at least we were able to hunt up scattered birds afterwards.

Your final option, assuming you’ve closed the range to within shooting distance, is to fire a shot in the air to make the birds flush. That’s one reason I like to hunt Gambel’s Quail with a lightweight semiautomatic shotgun. You’ve still got two shells to play with after firing the “flushing shot.” This can be a good tactic to employ if you’re hunting with dogs. Gambel’s seldom hold tight for dogs, but once flushed, you can send the dogs in to hunt up the singles and doubles.

Of course, Gambel’s Quail can employ a few additional countermeasures. Their favorite is what I like to call the “gradual Houdini.” This happens, with predictable frequency, when you’re hot-footing it after a covey, trying to close the distance. Over time, you notice that the covey appears to be getting smaller and smaller until it disappears altogether. Don’t assume that the birds simply outran you. In all likelihood, they were peeling off, one or two at a time, and holding tight while you ran past. The cure is to work right back over the ground you just covered. Do so quickly, for it doesn’t take much for these birds to start running again.

Regardless of which quail species you decide to hunt, give the birds a sporting chance. Don’t pursue a covey after sunset; give them time to roost as a group, rather than as isolated birds which are more vulnerable to predators. Likewise, don’t pursue the same covey relentlessly all day long. The birds need to eat, drink and rest, just as we do. Grant them that much respect as the fine game birds they are.

Mike Dickerson is a long-time, West Coast-based outdoor writer. He has fished from Florida to the Indian Ocean and hunted extensively across the United States and parts of Canada. He specializes in big game and upland game birds. You can contact him at letters@shotgunlife.com

Mike Dickerson is a long-time, West Coast-based outdoor writer. He has fished from Florida to the Indian Ocean and hunted extensively across the United States and parts of Canada. He specializes in big game and upland game birds. You can contact him at letters@shotgunlife.com

Comments