Women and Shotguns

Caution ladies: If your husband or boyfriend hands you one of his old shotguns for a round of clays shooting, say “Thanks but no thanks.”

Anecdotal evidence points to the above situation as a sure-fire way for a woman to never pick up a shotgun for the rest of her life. Why?

Shotguns are made to fit the average right-handed guy who stands 5-foot-9, weighs 165 pounds, has a 33-inch arm length and wears a size 40 regular. That means the gun will be too big for most women. The result is a massive recoil-driven thrust to your shoulder and cheek bone that will hurt for a very long time and likely cause some bruising. Who needs that, right?

If you are truly interested in the proper way to learn wing and clays shooting, forget your significant other and his shotgun, and instead find a professional instructor. Here’s what to look for in an instructor:

- An inventory of shotguns that will fit women and children. Chances are, if you have a particularly small frame, a youth gun will fit you better than an adult sub-gauge shotgun such as 20 gauge and 28 gauge.

- You’d be advised to find an instructor who has been certified by the National Skeet Shooting Association (NSSA) or National Sporting Clays Association (NSCA). That’s because part of the curriculum includes effective communications with women. The instructor will need to touch you when it comes to mounting the gun, foot position and checking for gun fit and so it’s important that etiquette is observed.

- Some instructors will trot out their collection of tournament trophies as proof that they know how to shoot. What’s more important, however, is their ability to effectively communicate, otherwise you’re wasting your time and money. If they can’t articulate an idea in a clear manner, who needs them?

Shotgun Fit for Women

The typical shotgun is likely to hurt when you pull the trigger due to recoil. This is not necessarily the result of the recoil itself, but because the shotgun isn’t properly positioned against your body to manage the recoil. Compared with men, women have longer necks, shorter arms, bigger breasts, smaller hands, higher cheekbones, weaker muscle groups and compact skeletons. Each one of these anatomical differences has an impact on your ability to handle an off-the-shelf shotgun. Having a shotgun that fits you correctly can make all the difference between enjoying and reviling the shotgun sports.

You shouldn’t have to mash your face against the stock or stretch your arms to shoot a shotgun. The shotgun should fit you, not vice-versa. As a woman, here are vital points you need to consider in owning a well-fitting shotgun that reduces excessive bruising while at the same time increases your chances of successfully hitting a target.

A shotgun meets your body at five points: recoil pad against the shoulder, cheek against the stock, trigger hand on the grip, trigger finger on the trigger blade and left hand (for righties) on the forend. If all of these points are in proper alignment, the gun should feel comfortable, be easy to swing and allow your eye to form a straight line down the rib. Ultimately, you want a comfortable shotgun that shoots were you look (remember you point a shotgun but aim a rifle).

Therefore, five important shotgun stock dimensions that need to be evaluated specifically for women:

- Cast (angle of the stock relative to the axis of the barrel). You want the cast to be “toe out.” Toe out cast dictates that the recoil pad will be angled outward, toward your shoulder, for a more natural fit in that area to help reduce felt recoil around the breasts. Cast can also be addressed with an adjustable comb which is a cut-out in the stock that lets you set the cast and height. As an aside, make sure your bra strap doesn’t rest under the recoil pad since that could cause bruising.

- Pitch (angle formed by the butt of the stock in relation to the barrels). Women should have a positive pitch on their shotgun stock. For men, the typical pitch angles the recoil pad down into their arm pit area. For women, it should be the opposite given the shape of their body around the breasts. The pitch should reflect the contour of the point where the recoil pad fits into “the pocket.” A simple wedge shaped insert between the recoil pad and the stock butt can inexpensively provide the correct pitch.

- Length of pull (length of the stock as measured from the middle of the trigger finger to the butt). Length of pull is often the quickest fix to women shotgun fits. It simply involves cutting the stock from the back to make sure your trigger finger is well-positioned. In some cases, shortening the stock may be sufficient. However, do not take for granted that length is the only dimension that needs attention. Also, pay attention to the balance of your shotgun after the stock is cut. You could find yourself with a barrel-heavy shotgun that is difficult to swing. If so, consider adding weight into the stock to achieve perfect balance around the hinge pin. For example, you may be able to insert an after-market recoil reducer that adds necessary ballast while using either mercury or springs to absorb recoil.

- Drop at the comb (distance of the angle formed between the barrel rib and the comb and heel of the stock). Because women generally have longer necks than men, they should look for a shotgun with a Monte Carlo stock, which is easy distinguished by a bump-up that raises the comb. Some Monte Carlo stocks also feature an adjustable comb — a cut out section that can be altered for drop and cast. An adjustable comb will let you raise the stock to the appropriate height.

- Drop at heel (the distance from the plane of the rib to the stock’s heel). Long-necked shooters such as women would need additional drop at heel. However, other aspects need to be considered such as slope of the shoulders and forward-leaning gun mount which would contribute to less drop at heel.

How to Reduce Shotgun Recoil

Fire a shotgun and the gas from the ignited powder forces the pellets out of the hull, along the barrel and toward the target — with an equal reaction manifesting itself as felt recoil.

If your shotgun weighed as much as your shotshell, the felt recoil would be unbearable. But your shotgun doesn’t weigh in at two ounces; it weighs six to eight pounds. The added weight of the shotgun absorbs most of the felt recoil — but not all of it.

The way the math works is that if you increase the weight of your shotgun by 10%, you could cut felt recoil by about 10%. Conversely, if you opt for a lighter gun you will increase your felt recoil. This proportion is not always linear, but it does provide a satisfactory theory for your average shotguns and shells.

Gun weight is not the only way to reduce recoil. A reduction in muzzle velocity or shot load can yield impressive felt-recoil reductions. Trim your 3-dram, 1200 feet-per-second (fps) shotshell by 10% to a shotshell of 1080 fps, and you could find yourself trimming felt recoil by some 20%. The same with shot load. If you reduce it from 1½ ounce to 1 ounce you could realize nearly 19% less felt recoil. While shot-load correlation may not consistently be 2:1, it gives you a good idea of what’s possible with other alternatives.

Gun weight and shotshells are certainly a good place to start with your felt-recoil problems. But if your shotgun doesn’t fit properly, any gap between the butt stock and your body is going to aggravate that equal and opposite reaction — regardless of anything else.

For many women, the problem with moving to a heavier gun is their upper-body strength. With the average men’s shotgun weighing 7-8 pounds, shooting a box of 25 shells at clay targets can be downright exhausting — the problem compounded by the onslaught of that equal and opposite reaction. However, a heavier shotgun requires greater strength in the arms and shoulders. That’s why so many women shoot semi-automatic shotguns: the semi-automatics bring a reasonable weight to the game while at the same time can potentially reduce felt recoil better than an over/under.

Your score and your shooting form suffer. Try to shoot a shotgun that’s too long and you’ll find yourself leaning back — the complete opposite of a well-balanced shooter who is supposed to rotate off her front foot. Try to shoot a shotgun that’s too short (let’s say a youth shotgun), and you could find your face creeping up the stock, and screwing up the alignment between your eye and the beads.

How About a Semi-Automatic?

Semi-automatic shotguns — or autoloaders as they’re also known — are prized for their low felt recoil compared with over/unders. A semi-automatic uses some of the expanding gases from the fired shell to cycle the next one into the chamber. So rather than you absorbing the full force of the shot, a semi-automatic puts that energy to good use.

Another type of semi-automatic is inertia-driven. Rather than using the gasses, this type of shotgun actually harnesses the recoil to reload the chamber. However, some people complain that inertia-driven semi-automatic shotguns can kick harder than gas-operated semi-automatics.

Semi-automatics don’t eliminate felt recoil, but they can reduce it by up to 40%.

Should I Buy a Sub-Gauge Shotgun?

Generally speaking, the smaller the gauge the lower the recoil. The 20-gauge shotgun is often a great alternative to the standard 12-gauge shotgun for women shooters. The 20-gauge shotgun provides nearly as much firepower, but with lower recoil.

Nearly every shotgun maker has a wide selection of 20-gauge models — including everything from over/unders, side-by-sides and semi-automatics. You can find 20-gauge shotguns for clays and wingshooting at about the same prices as 12-gauge.

While 12-gauge ammo is typically the cheapest available, the price of 20-gauge is often comparable. Once you go below 20 gauge, however, ammo prices climb steeply.

For women unconcerned about ammo prices, the 28-gauge shotgun can be a wonderful experience. The 28-gauge shotgun typically has the recoil of the tiny .410 with the breaking power of a 20-gauge. Commercial ammo can be difficult to find, however. Since most big-box stores cater to waterfowl hunters, the bigger gauges tend to fill the shelves. You can find 28-gauge, it’s just that the selection won’t be as large and the price premium can be double.

So before jumping into a 12-gauge shotgun, explore the world of smaller gauges. They can often give you an extremely satisfying shooting experience without knocking you around.

What About Low-Recoil Ammo?

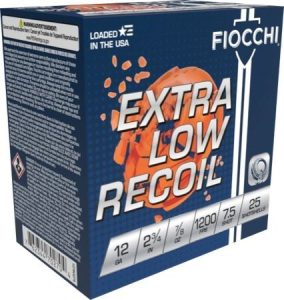

You’ll find companies such as Winchester, Remington and RST make special low-recoil shotshells. These are among the most successful solutions to make recoil livable.

In addition to low recoil, they are quieter — delivering an overall pleasant shooting experience. If you’re going to experiment with these loads, they should be used for targets. These low-recoil loads can be upwards of 20% slower than your normal load. Use them on birds and you could end up with plenty of cripples.

You can easily break as many targets with these low-recoil loads as with conventional ammo when it comes to skeet and 16-yard trap. You may even find they work well on handicap trap up to about 20 yards.

But bear in mind that the velocity of these loads is typically no faster than 1,000 fps. You may find some low-recoil shotshells can travel in the 1,100-fps range, which is more than sufficient for clay targets and smaller game birds.

Do Recoil Pads Really Work?

The answer is a resounding yes. But the benefits vary greatly from shooter to shooter.

Recoil pad and manufacturers claim reductions in felt recoil from 40% to 95%. The numbers are all over the place, not because they are misleading but primarily the measurement of felt recoil depends so much on the action of the shotgun, how the shotgun fits and the body of the shooter.

The science of shotgun recoil has become an industry. Some companies enhance your basic rubber pad while others use hydraulic technology that puts the principles of your car’s shock absorbers on the butt of your shotgun stock.

The black recoil pad at the end of the shotgun stock can be a valuable tool for women in reducing recoil, depending on the softness of the material used in the pad. The recoil pads are available in different thicknesses and can also be used to adjust the length of the shotgun.

Then there’s the other kind of recoil pads that fit along the comb to cushion your cheek from felt recoil. Mostly, though, when the discussion turns to recoil pads the implication is that you’re talking about the kind that sit between your stock butt and shoulder.

The underlying physics of all recoil pads is that they compress when you shoot, absorbing the felt recoil and reducing the jolt to your shoulder. Instead of a sharp jab you feel a gentle shove.

Some pads will easily fit right onto your shotgun. They could be predrilled to fit into the existing holes. Better yet, you could buy a slip-on recoil pad that doesn’t need any tools. But if you want something permanent and less noticeable, you have to go for the rubber or gel pads that mount on the butt of the stock. Taking this route can be more expensive. Unless you manage to find a direct-fit replacement, the rubber pad in particular can be ground down for a perfect fit — and that typically requires the expertise of a stockfitter.

The same is true of hydraulic recoil systems. This approach couples the traditional rubber pad with hydraulic shock-absorbing cylinders. The cylinders compress — protecting you from the rearward thrust of the shot. Often, these systems let you adjust the amount of compression for maximum comfort and fit.

Hydraulic recoil pads are longer than the rubber or gel recoil pads — making a stock cut mandatory in most installations.

Any time you add a recoil pad to the stock, unless it’s a perfect factory fit, you’re going to alter the dimensions of the stock –and in turn change the fit.

The same is true of cheek pads. They slip over the comb of the stock to cushion your cheek against recoil. The downside is that the cheek pad raises your cheek on the stock — throwing off the line of sight between your eye and the beads. In effect, cheek pads made your stock higher.

They can be helpful if in fact you need a higher comb and don’t have a stock with a cut, adjustable comb. Use it for recoil, though,and you’ll need to consider the implications of using one.

Just remember, any changes you make to the stock of your shotgun will definitely impact your score. Be prudent in your choice, because some of them may be irreversible.

Are Mechanical Recoil Reducers a Good Option?

What we’re talking about here are products that use springs and mercury to absorb recoil. The difference between other recoil suppressors is that these devices fit into the stock of your shotgun.

If you remove the recoil pad from your shotgun, you’ll probably find a deep hole at the bottom which is the bolt that fastens your stock to the receiver. There’s usually enough room in that hole to insert a recoil reducer.

In the case of the mercury-based offerings, they shift the mercury to the rear of the cylinder when you pull the trigger — in effect using inertia to counter the recoil.

It’s difficult to say which design works better — springs or mercury — but one is certainly quieter than the other. The spring products can “boing” — a potential distraction.

Chances are you’ll find either a spring or mercury anti-recoil device to fit straight-away. Make sure you measure the hole in the stock first before making your purchase. In most instances, these are a do-it-yourself fix. You merely need to unscrew the recoil pad and drop it in.

You need to be aware that both these designs add weight to the stock and could significantly alter the dynamics of your shotgun. But since they are relatively low risk, you may be willing to give them a try.

The other alternative is to buy a weight that fits on the barrel of your gun. The theory is that any extra weight serves to absorb recoil. For skeet and trap shooters, the additional weight gives you momentum when swinging your shotgun — giving you a swing-through boost (especially helpful if you tend to stop your gun before completing the swing).

The downside is that suddenly you have a heavier gun, which poses a problem for longer shooting sessions.

Irwin Greenstein is Publisher of Shotgun Life. Please send your comments to letters@shotgunlife.com.

Comments