There are no signs on the factory at 420 North Walpole Street in Upper Sandusky, Ohio, but open the old door and the pungent smell of machine oil is your first hint that the Ithaca shotgun is being re-born.

This rambling building that once housed a rolling rink, an automotive center and mold-making operation has been transformed into the backbone of the Ithaca Gun Company. Hard-working American men and women, like so many discarded in the upheaval of globalization, are now devoting their full measure of sweat and muscle to manufacture a new 100-percent American-built over/under shotgun code-named Phoenix.

“It’s nice to think that we could help our brothers and sisters in America by keeping and creating new jobs,” said Ithaca machinist, Tom Troiano.

Every screw, spring and steel billet is sourced from the U.S. as the company brings to life the stunning new 12-gauge Phoenix. From its inception, the Phoenix was designed to honor the proportions and sturdy sensibility of the classical over/under American shotgun.

Ithaca’s Phoenix in-the-white.

Shotgun Life recently enjoyed the privilege of spending a full day at Ithaca talking with nearly everyone in the company. We spoke with the men who made the barrels, the receivers and the stocks. We spent time with management. And we were given the unique opportunity to be the first one outside of the company to shoot a prototype of the forthcoming Phoenix.

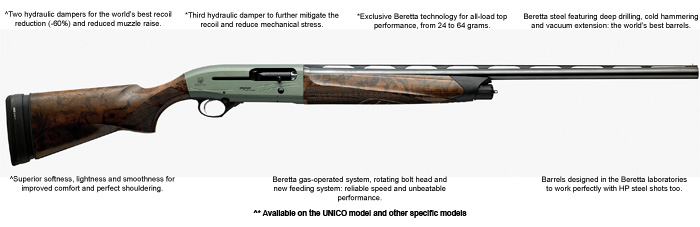

We can report unequivocally that design breakthroughs engineered into the Phoenix have made it the softest shooting 12-gauge over-under we have ever pulled a trigger on. The felt recoil on the Phoenix is virtually nonexistent – on par with the benchmark Beretta 391 Target Gold 12-gauge semi-auto – kicking only just enough to reset the inertia trigger.

Better yet, with a starting price of about $2,500 and moving to $10,000 depending on the type of engraving and grade of American walnut, the Phoenix could easily mark a renaissance of the big Ithaca shotguns.

That’s why Ithaca named the Phoenix after the dazzling mythical bird which rose from the ashes to fly once again. But leading Ithaca authority, Walt Snyder, author of the definitive books The Ithaca Company From the Beginning and Ithaca Featherlight Repeaters…The Best Gun Going observed that the new Phoenix also has an historical precedence.

In 1945, Ithaca had built a one-of-a-kind 12-gauge, over/under prototype. As the Model 51, it had serial number EX1, for experimental 1. It now appears that the new Phoenix is a direct descendant of that orphaned masterpiece.

The Phoenix as we saw it at the Shot Show.

Our first glimpse of the new 12-gauge over/under took place in January 2009 at the expansive Shot Show. There in booth 1736, I was drawn to the allure of an elegantly understated over/under that was all chrome-moly black steel and American walnut. The receiver, devoid of engraving, drew me in and I picked up the gun. I mounted it to my shoulder, my immediate impression one of a tight, well-balanced shotgun. Then I moved the top lever to the right and to my astonishment the barrels slowly fell open as though on hydraulics.

This was the shotgun that Walt would see several months later at a dealer event in Wilmington, North Carolina. Ithaca’s Mike Farrell arrived with it and Walt’s initial impression was that “It looked like a very well made gun. It seemed to mount and balance very well.”

At the time of the Shot Show, the gun remained months away from being in shooting condition and it hadn’t been christened the Phoenix. But after returning to the office, I would occasionally call Mike, the company’s number-two guy (no one at Ithaca has a job title), until he agreed to let me visit the company and actually try the shotgun.

For those of you familiar with Ithaca shotguns, it would be easy to dismiss the Phoenix as another heartfelt effort to salvage this fabled American manufacturer established in 1883.

Taking its namesake from the first factory in Ithaca, New York, the company’s fortunes in later years have been a tortured tale of missteps as one management team after another tried to reclaim the glory years that spanned the late 1800s until Pearl Harbor. That was a triumphant epoch when Ithaca manufactured shotguns such as the Flues side-by-side, the Knick trap gun, the 3½-inch Magnum 10 and the Model 37 pump based on a design by John Browning.

Beginning in the late 1960s, the company changed hands several times until it padlocked the doors in1986. The following year a new investor group took the helm until 1996, when entrepreneur Steven Lamboy acquired the assets and rights to make the Ithaca doubles. He turned out some beautiful shotguns in Italy bearing the Ithaca name but fell into bankruptcy in 2003. By 2004, the Federal government attached the company’s bank accounts for back taxes and a bitter lawsuit ensued in New York state between various stakeholders. In 2005, Ithaca’s assets were surrendered and the company liquidated.

That’s when Craig Marshall entered. Owner of MoldCraft in Upper Sandusky, he converted the family mold-making business into a new iteration of Ithaca. During the transition, the Marshalls assembled the flagship Model 37 pumps from existing inventory with every intention of restoring the marque’s luster. Unfortunately, the Marshalls eventually found themselves under-capitalized for the venture to the extent that they were forced to idle the factory for eight months between 2006 and 2007.

Finally, in June 2007 industrial glass magnate David Dlubak acquired the company’s assets and Ithaca name from the Marshalls. He started making fresh plant investments in the nondescript Upper Sandusky facility and brought back the team working on the Model 37.

As Dave explained to us in Ithaca’s distinctly blue-collar conference room, “We want to make a high-quality shotgun, at an affordable price, that will fit in the working man’s hands. The gun is going to be that guy’s pride and joy. The old Ithacas lasted fifty or sixty years. Now we make them to tighter tolerances and with better steel. We don’t want cheaper, we want better.”

Like many luminaries in the industry, Dave did not get his start making shotguns. Just as Harris John Holland began as a tobacconist, and Charles Parker a maker of spoons, curtains and locks, Dave comes from a family that owns and operates one of the largest industrial glass recycling businesses in the U.S., Dlubak Glass.

Dave was in the process of finalizing a new product called “bubble glass” that combined concrete and glass in faux log building material. Replete with grains and knots, bubble glass is resistant to fire and insects but soft enough for an ordinary drill bit. He was looking for a mold maker who could package the bubble-glass logs for affordable and dependable shipment.

He went to MoldCraft and met the Marshalls. Dave was presented with an opportunity to invest in Ithaca. Instead, he bought it.

Although a long-time aficionado of Ithaca shotguns, he acquired the company because of “the quality of the people and their ability.” These tool-and-die makers were the “elite of the elite,” he said.

For example, barrel-maker Roger Larrabee has been a tool-and-die machinist for 47 years. He trained Tom Troiano, who turns out the receivers.

“Roger trained a lot of the guys here,” Tom said.

Ithaca craftsmen Roger Larrabee, Tom Troiano and Dan Aubill.

As a self-described “control freak” with a passion for quality, it was paramount for Dave to build a team with the capabilities to “make all the parts here,” he said. “I’m interested in making it all under one roof.”

He characterizes the Ithaca Gun Company as being in “stage two,” meaning that it has resolved the manufacturing issues with its current popular pump guns: the accurate Deerslayer series, the rugged Model 37 Defense, and the sweethearts of the pump-gun community, the 28-gauge Model 37 and the Model 37 Featherlight and Ultralight.

These shotguns showcased the production capabilities of the company. They demonstrated the team’s ability to craft receivers from a billet of steel or aluminum, to do away with soldering or any other heat-inducing joining, and to machine one-piece barrels with integrated rib stanchions that eliminate any potential warpage from the run-of-the-mill rib soldering.

“Ithaca certainly seems to have manufacturing savvy,” Walt said. “I’ve seen their Model 37 and it’s beautiful and I would assume they would be successful with the new over/under.”

These accomplishments came from “spending many midnights sorting these things through,” Dave said. “We’re not in love with wood, we’re in love with steel.”

The company’s passion for steel is clear when you tour the factory floor. As raw Pittsburgh steel goes from the mill-turn lathes to to grinders to finishing machines to polishers there is an almost monastic sense of duty among the people making parts for the shotguns. All the tooling and fixturing was developed in-house. Custom software was written by the youngest guy on the crew for the tightest possible tolerances. The individual components are funneled into an assembly room where one person hand fits everything together into a single shotgun.

After the factory floor I spent time with Aaron Welch, Ithaca’s designer and engineer. Looking over his shoulder in the cramped office, he rotated the solid-block 3D models of the Phoenix on his computer monitor.

There was the Anson-Deeley boxlock action ready to fire 2¾ inch shells.

I discovered that a secret to the low recoil of the Phoenix are the three capsule-shaped pockets machined into the bottom of the receiver. They are designed to distribute the load of shooting, improve longevity of the components and help absorb the spent gasses. Moreover, the slightly greater mass of the receiver and monobloc combine to give the Phoenix a lower felt recoil. The less-restrictive 1.5 degree forcing cone and somewhat heavier burled stock also helped tame excessive kick.

In examining the monobloc, Aaron talked about how the barrels are held to the breech section by a tubular connector, instead of being soldered, to improve reliability. At the business end of the 30-inch barrels, the muzzles are dovetailed together, rather than soldered, to prevent distortion from thermal expansion.

That sense of a hydraulic assist when opening the shotgun comes from cocking rods that push against the hammer springs when you move the top lever.

The top bolting mechanism was borrowed from the old Ithaca Knick. It sits high in the receiver for a stronger grip on the monobloc.

Next I looked at how the rib slides into the stanchions and is mounted with a single screw. Aaron said that interchangeable ribs would be available to provide different points of impact.

In the end, the Phoenix would weigh about eight pounds.

Now it was time to see how all the parts worked together.

Dave Dlubak with the Phoenix prototype.

Mike grabbed the prototype of the 12-gauge Phoenix. The shotgun was still in-the-white with a couple thousand test rounds through it.

We drove a few minutes to a piece of property on a lake that had once been a quarry. A house overlooking it was under construction. The house belonged to Dave and was being built from bubble glass in cinder-block form factors.

In addition to the house and lake, the property also had a trap machine set up by the previous owners.

Mike handed me the gun and in fact it did feel very well balanced. I practiced mounting it a few times. The straight stock fit quite well. Dan Aubill, the guy in charge of Ithaca’s custom stock program, had told me that it was measured to fit the “average guy” with a 14¼ inch length of pull, zero cast, drop at comb of 1½ inch and drop at heel of 2¼ inch.

Pushing the top lever, the barrels slowly fell open. I loaded in two 1? ounce shells. Mike took up the controller and when I called “pull” two things immediately took me by surprise. The first was the extremely low recoil, the second is how I completely pulverized the targets.

Mike and I went through a couple of boxes of shells, the two of us taking turns pulling targets. The trigger was light and crisp, the beads lined up perfectly and the tapered forend enabled a wide range of control.

I turned out to be the last one who shot the Phoenix that day and when the time came to return it to Mike I thought “I gotta get one of these.”

Irwin Greenstein is the Publisher of Shotgun Life. Please send your comments to letters@shotgunlife.com.

Useful resources:

http://www.ithacagun.com