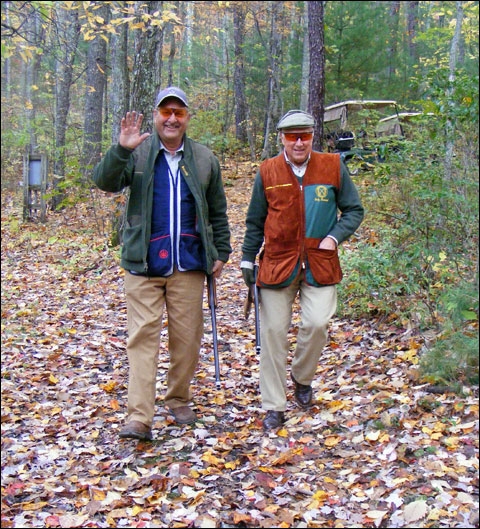

Cigar smoke mingled with fragrances of autumn, marking the twenty-first annual weekend of convivial sporting-clays competitions in the mountains of Virginia by the exclusive Green Jacket Club.

Cigar smoke mingled with fragrances of autumn, marking the twenty-first annual weekend of convivial sporting-clays competitions in the mountains of Virginia by the exclusive Green Jacket Club.

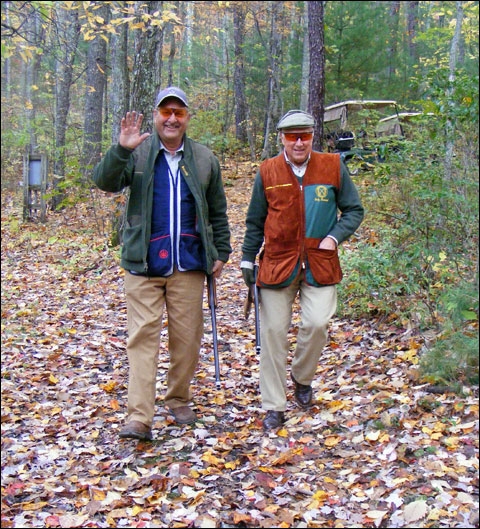

Our friend Silvio Calabi gave us a heads up that the book he co-wrote called “Hemingway’s Guns: The Sporting Arms of Ernest Hemingway” was about to be published. Having seen some of the chapters in advance, we were excited about the new information revealed from the in-depth research. Silvio gave us permission to run a chapter titled “The Winchester Model 21 Shotguns,” which appears following the introduction below.

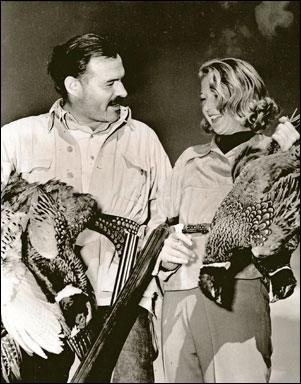

[caption id="attachment_1653" align="alignnone" width=""] A rare snapshot of Michael McIntosh.[/caption]Michael McIntosh, one of America’s foremost shotgun writers died on Saturday, August 14, 2010, at his home in Iowa. He was 66 years old.

A rare snapshot of Michael McIntosh.[/caption]Michael McIntosh, one of America’s foremost shotgun writers died on Saturday, August 14, 2010, at his home in Iowa. He was 66 years old.

Other people called him Mike, but I never did. To me, he was always Michael – and if a finer friend than Michael McIntosh ever existed, I have yet to meet him.

Harold Stoneberger sets a trap machine for a 3-bird shoot the following day.[/caption]

Harold Stoneberger sets a trap machine for a 3-bird shoot the following day.[/caption]This story is the first in an occasional series called “Confessions of a Target Setter” where we speak with the men and women who try to confound us at every turn in sporting clays.

It’s August 27, 2010 and the summer heat wave that wracked the country seems to have finally broken here in the hamlet of Wellsville, Pennsylvania – home of Central Penn Sporting Clays. Owner Harold Stoneberger and his young helper, Ben Rickland, are scrambling to set targets for a 3-bird shoot the next day, and I’m here in the field with them as they share their tricks of the trade racing from one trap machine to the next, wrench in hand.

Common wisdom says one thing, Bobby Fowler Jr.’s trophy case says another.

Since he first started shooting competitively in 1993, Fowler has won about 150 titles in sporting clays and FITASC. He’s dominated the sports so thoroughly, that his middle initials should be HOA. Every gauge, on both sides of the Atlantic, in his home state of Texas – no tournament is safe from Fowler’s monumental skills in achieving the highest overall average.

Story and photos by Mike Childress

Last Friday was atypical. I got an invitation from my brothers- and father-in-law to come out to the property and take my chances against clay pigeons thrown from the back of an old International Harvester pick-up.

It’s been a while since I shot clay birds. More than a little while actually, from the days my dad and I used to reserve our Sundays for the local trapshooting club. And, after a day of office work, it was a welcome change. After rummaging around for what seemed like an eternity I found my shotgun, shells, and even some “birds” that my father-in-law had given me for a birthday present the year before, still unopened. My wife and I made quick preparations for the 15-minute trek north. Car seats, check. Diaper bag, check. Guns and ammo, check. We were off.

Wouldn’t it be great if four-time Olympic shooting champ Kim Rhode finally appeared on a box of Wheaties?

As legend has it, if it had been up to Wayne LaPierre, Executive Vice President of the National Rifle Association, Kim would’ve been beaming her warm smile on the Breakfast of Champions back in 1996, when at age 16, as the youngest member of the U.S. Summer Olympic Team, she won her first Gold Medal for double trap.

Anyone who shoots a 16-gauge shotgun should send Doug Oliver a big cigar.

As founder of the 16 Gauge Society, Doug has been keeper of the flame for a shotgun orphaned by the industry.

Over the years marketing decisions within the shotgun industry have relegated the 16 gauge from the second-most popular shotgun to an icon of perfection among a small band of bird shooters. They marketed the smaller 20-gauge rival, despite the superior ballistics of the 16 gauge. At the same time, the 12 gauge has been gentrified from its bruiser, meat-market heritage to a relatively comfortable, all-purpose shotgun.

The world of tournament shooting has also conspired against the 16 gauge. Simply put, there are no 16-gauge competitions in major clay-shooting events – depriving the 16 gauge of the credibility and high-profile marketing opportunities to sustain a thriving market.

Still, the perseverance of devoted 16-gauge shooters has kept the shotgun alive. And you could easily make the case that Doug has emerged as the voice of the 16-gauge shotgun community.

“If I were trapped on a desert island, I would want the 16 gauge, because it won’t beat you up and it kills birds without killing you,” Doug said.

Maybe it’s a confluence of happy circumstances that Doug, who owns a graphic-design firm in Bell Canyon, California, fell in love with 16-gauge shotguns to the extent that he started the 16 Gauge Society web site.

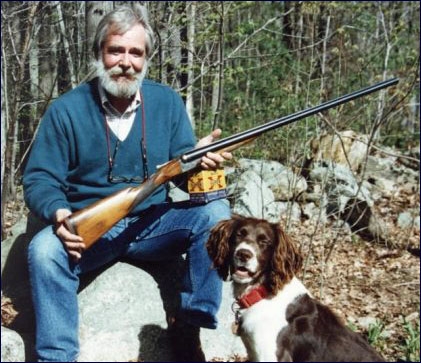

Doug Oliver

He fondly recalls shooting 16-gauge shotguns as a kid in Newton, Kansas with his father.

“From the age of 10, I started hitting birds, and I became joined at the hip during bird season with my father. We’d hunt quail, pheasant, doves…,” he said.

During that period, he started out with a .410, and passed through a 16 gauge on his way to a 12 gauge. He remembered liking the 16 gauge, although for the bigger part of his life he shot 12 and 20 gauge.

“The 16 gauge is absolutely the perfect shotgun,” he explains. “It has a perfect load for wingshooting. Plus a 16 gauge will typically be a pound lighter than a 12 gauge if you’re carrying it all day in the field. The 16 gauge shoots like a 12 gauge but carries like a 20 gauge. It’s a great gun.”

When Doug turned 50, for his midlife crisis instead of a Porsche he bought himself a shotgun. It was a 16-gauge F.A.I.R. Rizzini over/under. It was a better gun than he had known at that point.

On a flight from Los Angeles to New York, he had been reading an article in Double Gun Journal about dove hunting in Argentina. Until that point he had every intention of buying a 20 or 28 Beretta, but the article deflected him to the 16-gauge F.A.I.R. Razzing.

Doug found himself smitten by the lovely 16 gauge. In doing his “homework” for that 16-gauge F.A.I.R. Rizini he realized “that 16 gauge was a stepchild,” he explained. “Information at the time was so hard to dig out and that’s where the 16 Gauge Society web site came in. I though I’d just design and throw up 16 gauge web site and maybe sell a couple of hats. The project itself was fun and informative.”

After a few months of hard work, the 16 Gauge Society web site went up in 2002 at http://www.16ga.com.

It now has approximately 1,500 members of the 16 Gauge Society, plus another 2,400 people who frequent the site’s forum which serves as a clearing house of information for everything 16 gauge. Over 60,000 posts have been recorded on the site.

As Doug relates about the forum “You can throw a question out about a gun and 10 guys will answer you – civilly.”

There is a one-time, lifetime $25 membership to the 16 Gauge Society. But for Doug, the organization “is not a moneymaker. It’s a passion.”

Last autumn, one of the members of the 16 Gauge Society organized a pheasant shoot in North Dakota. A dozen or so members met for the first time there. “It was fun, everybody got pheasants,” he said. “A good time was had by all.”

In a way, that was a trip back to the good old days of 16-gauge hunting.

Doug is an active 16-gauge shooter. Of the 10 shotguns he currently owns, four of them are 16 gauge. He still has that F.A.I.R. Rizzini, in addition to a 1959 Beretta Silverhawk and two Browning Sweet 16 A-5s.

He recalled that when he began hunting there were a lot of 16-gauge shotguns on the market. Winchester Model 12s, Ithaca and Remington pumps, and the Browning Sweet 16 A-5s dominated the market, alongside a smattering of Fox, Parker and L.C. Smith doubles.

Although many a young hunter was started in the field with a 16 gauge, by the late 1950s and early 1960s, the 20 gauge, and later the 20-gauge 3-inch magnum, simply buried the 16 gauge shotgun in the U.S.

Doug now thinks that the 16 gauge is experiencing a renaissance. “After a 50-year decline in popularity, the sixteen is making a well-deserved comeback. And in a number of production lines, too.”

Today, although sometimes difficult to find, the industry still offers the standard and high-velocity lead and non-toxic loads from all major manufacturers. “Yet even though this situation has improved in the last few years, most serious 16-gauge shooters custom hand load their own shells. This is true of many shooters regardless of gauge,” Doug observed.

Affordable 16-gauge shotguns are available from a number of manufacturers including Griffin & Howe, Arietta, A. H. Fox, Browning, Connecticut Shotgun Manufacturing Company’s Model 21, Cortona, Arietta, Dean, Grulla, Stoeger and a handful of others.

And of course, there are also thousands of used 16-gauge shotguns in search of a new home.

Noe Roland is a frequent contributor to Shotgun Life. You can reach him at letters@shotgunlife.com.

Useful resources:

http://www.arrietashotguns.com/

http://www.connecticutshotgun.com/ahfox1.html

http://www.connecticutshotgun.com/model21.html

http://www.cortonashotguns.com/

http://www.grullaarmas.com/es/

http://www.stoegerindustries.com/

{loadposition signup}

Most people agree that baseball is the all-American sport. But after spending three days in San Antonio, Texas at the National Shooting Complex, I would argue that the sport which best captures the heart and soul of the American spirit is skeet.

Professional baseball has been battered by drug scandals, crass commercialism and outrageous salaries – giving a black eye to the American core values of fair play, self-determination and mutual respect.

By contrast, tournament skeet remains firmly in the stronghold of the shooter who competes for the love of their sport and a burning desire to win fair and square. While these birds certainly don’t have feathers, the hunger is still there to feed that great American quality of redemption – that you can always pick yourself up by the bootstraps to make a comeback target by target. It’s the grit of the individual and their gun forging their own destiny.

While professional baseball now finds itself pulsing through the digital infrastructure onto big-screen TVs and multi-media web sites, skeet holds fast to the ideals of craftsmanship in the hand-finished shotguns that still produce a streak of 500 or more consecutive broken targets.

Although the predecessor to the baseball bat may have helped primitive man fend off sabre-tooth tigers, it is the gun that won the American West – a part of the country I found myself in for three days in March.

As an avid recreational clays shooter, I became immersed in tournament skeet through a remarkable program developed by the National Skeet Shooting Association (NSSA) – the sport’s nonprofit governing body.

The NSSA and its sister group, the National Sporting Clays Association (NSCA), in conjunction with the state-level associations, keep track of just about every major skeet and sporting clays tournament in the U.S. The NSSA-NSCA is the repository for all registered scores shot in both large and small clubs throughout the country and in the world.

NSSA shooters often enter the realm of tournament skeet through grass roots organizations such as the 4H, which actively promotes skeet competition; through various instructors who want to see a promising student take their skills to the next level; or through local clubs where the NSSA sanctions competitive shoots.

But NSSA member, Stuart Fairbank, saw another way of opening the door of tournament skeet to recreational shooters. It’s called Shoot with the Stars, and it has been held at the annual Toni Rogers Spring Extravaganza, one of the earlier Top 10 shoots in the country that shooters use to open the tournament skeet season for three years. This year it took place March 27-29 at the NSSA-NSCA National Shooting Complex.

Although Stuart says the concept for this type of program had been around for the past 20 years, it was in 2007 that he teamed up with NSSA Secretary/Treasurer, Bob DeFrancesco, to really make it happen.

As Stuart explained it to me in the club house “There were always people who felt that the shooting games were exclusionary. They belong to a home club where they feel comfortable, but in terms of tournament shooting they have a hard time getting started. It can be confusing at first especially when you travel away from home and don’t know anybody at the shoot. And there’s the apprehension associated with meeting, and being squaded with, and competing against the big shooters. We want to make it as easy as possible for the new folks to experience a first-class tournament, meet and shoot with some of the best in the game, and do it all on manageable budget.”

For example, for someone like me who’s managed to shoot his fair share of 25 straight in skeet, it would be an absolutely intimidating proposition to go up against the likes of some of this year’s stars…

Of course registered tournaments do not directly pit the new shooter against these stars, or the other stars who participated in the program including John Shima, Stuart Fairbank and John Herkowitz. A classification system that ranges from top-ranked AAA to E shooters ensures competitive equilibrium. I had been ranked D, given that I had registered for a single tournament skeet shoot in 2007.

Turns out, I was exactly the kind of shooter that Stuart wanted to attract through Shoot with the Stars.

Stuart believed that the sport needed to create “ambassadors,” or recreational skeet shooters who were given the opportunity to mingle with the stars, and then go home and spread the good word.

So in 2007, Stuart and Bob posted the first Shoot with the Stars call on the Internet, attracting three shooters. Over time, a selection process was put in place. The names of up to 27 shooters would be drawn – three from each of the organization’s nine regional zones.

This year there were 15 recipients including myself, since I was the only one to apply from Zone 2.

The 2009 sponsors were Ms. Toni Ann Rogers (Title Sponsor), Federal Ammunition, Browning, Rio Ammunition, Kolar Arms, Remington Arms (.410 bore), Winchester Ammunition (28 gauge), While Flyer targets, leathersmith Al Ange and the NSSA as sponsors.

With sponsors and organization in place, the 2009 Shoot with the Stars gave us newcomers 100 shells in each gauge (12, 20, 28 and .410 bore) for use in the competitions, plus they waived our entry fees in each event of $50 and the nominal target fees that came to $6 per day. The Shoot with the Stars program also provided the experience of a lifetime (for skeet shooters this is tantamount to playing golf with Tiger Woods).

My Shoot with the Stars adventure started when I landed at San Antonio International Airport at about noon on March 26th. After renting a car, I headed directly to Blaser USA in San Antonio, the U.S. arm of the German manufacturer that makes the marvelous F3 shotgun.

Having shot an F3 before, I knew it would be the gun to shoot. Here’s why…

Norbert Haussmann, CEO of Blaser USA, had arranged for me to pick up the perfect 12-gauge model for Shoot with the Stars. It had a Monte Carlo stock complemented by an adjustable comb. The barrels were 30 inches in length. The lid of the hard case held three sets of Briley Revolution tubes in 20 and 28 gauges and .410 bore. Along with a full set of chokes, Blaser packages this F3 as the American Skeet Combo. And I have to say, it is really impressive.

After a Blaser tech tweaked the comb for me, the gun came up just right. If ever I were going to shoot a great game of skeet, this F3 would be the shotgun to make it happen.

Mother Nature, however, had other things in store.

Before leaving for San Antonio, I had checked the weather. It was supposed to be sunny, mild and in the mid-80s. It didn’t exactly turn out that way.

The next morning saw prevailing winds of 20-30 mph with gusts to 40 mph. For a flying disc such as a skeet target, winds that high create crazy turbulence.

Air density, drag coefficient, angle of attack – everything is up for grabs as the wind blew across the open, flat terrain of the National Shooting Center.

If the target is going with the wind, it can race out of the trap house with an afterburner burst, and then get driven into the ground even before it reaches the opposite house.

If the target is going into the wind, it can simply rise and stall – one of the worst things that can happen to a shooter who uses momentum to swing through for the target break.

Then there’s the ongoing debate as to whether or not it’s best to break a target in the wind sooner or later. Some experts believe that you should break the target as soon as possible before the wind knocks it off the line of trajectory. Others, meanwhile, say you should wait until the target adjusts to the wind before pulling the trigger.

All I can say is that conditions were not great to shoot the first event of the tournament, which was doubles (when the high-house and low-house targets are thrown simultaneously).

Of the 45 skeet fields at the National Shooting Complex, I was slotted to shoot on number 9. My squad star would be perennial All American Sam Armstrong from Maryland. At least it was a 12-gauge event (imagine if it was .410).

Introductions and hand shakes all around among the five squad members and we were ready to shoot. During the 100-round event, I was surprised at the ongoing chatter of encouragement. If someone made a great shot, the others shooters in the squad let him know about it. When you stepped up to the station, you were given a pep talk – “You can do it…come on, get in the groove, crush ’em now…”

Turns out it was the unspoken code among tournament skeet shooters. You helped your competitor achieve their fullest potential in the preliminaries and then faced him head on in the shoot-offs. This friendly banter contributed to a real sense of family among the shooters – even for a newcomer like me.

For Sam and the other highly ranked shots, doubles took on a beautiful cadence: BANG…1 Mississippi…BANG. It was the veritable heartbeat of doubles. Consistently, they knew the rhythm of the game and mastered it.

My final score was 57. Not great. It turns out, I made a couple of mistakes when it came to shooting in strong winds, which were explained to me over dinner that night with Sam and his friends at a Saltgrass Steakhouse.

First, by following the school of thought that says you break the targets close to the house in the wind, I held the Blaser further back than usual. The gun swung so beautifully, I figured it would be no problem nailing that target right out of the house before the wind could grab it.

I found out afterwards that you do just the opposite when shooting in the wind. You hold further toward the center stake. By reducing your gun swing, you stand a better of chance of breaking the target as it slows down, as opposed to attempting to shoot it when it comes accelerating out of the house.

Another mistake I made was shooting the target when it stalled in the wind. For example, if I were shooting the low 1, and it stalled right in front of me, I ended up missing the target. I was wondering how was that was possible? After all, the target was stopped dead; it was close enough to be hanging right off the brim of the cap. How the heck could I possibly miss that target?

The answer was simple: I had unconsciously lifted my face off the stock to look at the unusually high targets. Break that seal between your cheek and the stock and you’ll miss the target every time – even if the bird is dangling three feet in front of you.

My third mistake was trying to measure the target lead in the wind. If you look for the lead, you invariably take your eyes off the target – or worse end up glancing at the front bead. Either way, the target will get away from you.

OK, lessons learned. But would they stick? Let’s see how I would shoot the next day.

Right after the alarm clock went off, I checked the weather on my iPhone. Wind was blowing at 15 mph, with gusts reaching 23 mph. Certainly challenging, but not as daunting as the day before.

When I arrived at the National Shooting Complex that morning, one word dominated the communal conversation: wind. One of the stars confided later that he had not missed a single 12-gauge target since August 2006 – until doubles the day before when he shot a 98.

Other top shooters said “the wind got to me.” What did they mean by that? A strong, relentless wind can make you tense your muscles, slowing you down. Likewise, a sense of exhaustion sets in, both physically and mentally. Unlike them, I never expected to shoot 100 straight, often the threshold for entering the shoot-offs. While a 97 or a 98 would be great for me, it was unacceptable in the rarefied ranks of AAA skeet champs.

I had two events scheduled for that Saturday. I would shoot 12 gauge at 10:30 and 28 gauge at 3:00. I was optimistic. At least 12 gauge gave me the firepower for a wider margin of error in the wind. When it came to 28 gauge, I’d been shooting it for the past year at my local club. I think it’s the perfect gauge for skeet, and I had recently nailed my first 25 straight in 28 gauge.

Stuart Fairbank, a multiple World Champion from Connecticut, turned out to be the star of our 12-gauge squad. An affable guy, he really kept up the chatter – giving the squad a positive vibe through all 100 rounds. My final tally for the event was 81. I have to give ample credit to the Blaser for what I thought was a good score. It performed flawlessly, giving me great site pictures, a controlled swing and a comfortable shooting experience.

With a few hours remaining until the 28-gauge event, I paid a visit to the NSSA-NSCA Museum on the grounds. The museum included a history of skeet with wonderful artifacts. There were Hall of Fame Photos for both skeet and sporting clays and some entertaining videos to watch.

After the Museum, I walked across to the concession and ordered a tasty pulled-pork sandwich. I took the sandwich onto the patio and watched the other events as I ate.

At about 1:30, I installed the 28-gauge tubes from the trunk of my rental car. They went in like butter. After I shot two practice rounds, I knew 28-gauge would be intimidating.

Everyone says that regardless of the gauge, you always shoot the target the same way. Keep your hold points and break points consistent, whether it’s 12 gauge or .410. However, here’s the rub: A standard 12-gauge 1-1/8 oz shell with #9 shot holds about 658 pellets. A standard ¾ oz, 28-gauge shell with #9 shot has about 439 pellets – or nearly 50% fewer pellets. For the highly ranked shooters, the lower pellet count wouldn’t make that much of a difference. But I needed all the help I could get as the sundowner wind started to kick up, fulfilling the prediction of 23-mph gusts. In the end, I shot a 67.

My 28-gauge star was multiple World Championship winner Billy Williams from Montana, the only one of two shooters to score perfect 100’s in doubles the day before. Throughout the event, Billy was a master of encouragement, leading the squad in a chorus of positive banter. Even with my less-than-stellar 67, it was a joy to shoot in that squad. By now, I was starting to feel like an NSSA son-in-law.

That night, the Party on the Hill was held in the massive Beretta Pavilion. A Mariachi band entertained as free Mexican food, cocktails and beer from a keg were served. From this vantage point, you could look down across the great expanse of the National Shooting Complex and the Hill Country Beyond. It was a clays shooting paradise.

Sunday morning saw me slotted for two events. At noon, I would shoot 20 gauge with star, Bob DeFrancesco, NSSA Secretary/Treasurer and many time All American from Connecticut. My .410 event would take place at 4:30 with star, Dave Starrett, another multiple World Champion winner from Ohio. The weather was a hold-over from the day before: 14-mph winds, gusting to 25 mph. In the 20-gauge event, I scored a respectable 75. My score for .410 score came in at 63.

What did I walk away with from my Shoot with the Stars experience?

For one thing, I learned that Stuart was absolutely right about the experts who volunteered as this year’s stars. Every one of them was approachable, supportive and basically just a really nice person. Second, it rekindled my desire to shoot registered skeet at my local club. I discovered that the competition simply makes you shoot better. You keep a razor-sharp focus on the targets, you pay more attention to foot placement at each station and you shot the birds more aggressively – breaking them sooner. Finally, I learned valuable skills that I could apply just when I’m hanging out and shooting skeet with friends.

Tournament skeet is not for every shooter. But sometimes you just don’t know until you give it a try. Based on my experience, I would urge any skeet shooter to give tournament shooting a test drive. Join the NSSA and find a club near you that holds registered shoots.

In the end, I had only one regret about my trip to San Antonio: it was having to return the Blaser F3. That shotgun sure was a keeper.

Irwin Greenstein is Publisher of Shotgun Life. Please send your letters and comments to letters@shotgunlife.com.

Helpful resources:

In a riverfront honky-tonk deep in the South, the sliding doors open to the verandah, women sat on bar stools wistfully blowing cigarette smoke at the stars.

It was the kind of forlorn place where a man could bring his bird dog and let it curl up on the floor between the stools, and you could never tell which one stunk worse – the man or the dog.

Time was of no consequence in this place, here on the river, in the darkness, where the hours and minutes were marked by the bug zappers incinerating their random catch. Yes, the Universe was clearly at work, here, now, in this honky-tonk where men and women wandered in drawn by the Big Mystery.

I never did get the name of that bar, but there’s one thing I’ll always remember about that place. It was where I first met Jim and Bugsy.

Their table was heaped with the remnants of peel-and-eat shrimp and empty beer bottles. I’d accidentally bumped into a corner of the table on the way to the john, a bit sodden myself, when I whirled around to see Bugsy splendid in his Vintager apparel and Jim in a shooting vest and baseball cap.

They looked up at me – more startled than menacing. Both sported long, thick cigars, and I remembered what Freud once said.

Taking in the scene I thought “these men are my kind of men.” So I decided to hold it in and rather than hit the john, and asked, “Can you buy you gents a beer for the inconvenience?”

Bugsy broke out laughing and turned to Jim: “Can you believe this guy?”

Jim simply nodded, world weary and wise.

“Of course you can buy us a beer,” Bugsy shouted.

“Hefeweizen with a wedge of lemon?”

“Sure, why the hell not?” Bugsy shouted.

Jim simply waved his hand, as though to say, que sera, sera.

“Miss, oh, miss,” I called to the barmaid. “Three Hefeweizen with a wedge of fresh lemon, if you please.”

She was young and lithe with a tank tap and no bra and she leaned over into the ice box, drawing the attention of the great rough slab of tramp-steamer maleness, each of them shanghaied to this forsaken place, here on the river, and she put three long-necked Snake Venom Ales on the bar in front of me.

“We’re outta lemon wedges, handsome” she said. “Start a tab for you and your pals?”

“That would be excellent,” I said. “By the way, do you have any coasters?”

She turned away, and resumed her conversation with the burly men at the end of the bar.

“Hey, you gonna eyeball those beers all night or bring ’em over here?” Bugsy said.

“Sorry about the coasters,” I said sitting down. “Fielding-Clapp, Cletus.”

“Bugsy.”

“Jim.”

Bugsy had a mischievous glint in his eyes, his face part pugilist, part English professor. Jim wore a scruffy beard, his dark penetrating orbs awash in a secret sea of resignation whose powerful tides shifted with the whims of Lady Luck. I couldn’t help but notice he wore an orthopedic shoe with a platform sole; one leg was longer than the other.

Their cigar smoke enshrouded us in a place within a place, here on the lazy river. The bar opened directly on to the water, giving the impression that we were on a slow boat to the end of the world.

“Shrimp?” Bugsy asked, pushing the plastic basket toward me.

“That’s extremely generous,” I said, “but I have a shellfish allergy.”

“No worries,” Jim said. “I always carry antihistamines.”

I put forth a polite smile. “So I see you chaps are into shotguns.”

Bugsy broke out laughing. “Hey, this guy’s a regular Sherlock Holmes,” he said to Jim.”

“Don’t start,” Jim said.

“Actually, I write for Shotgun Life.”

“I love it,” Bugsy shouted. “Man, we’ve got something for you to write about.”

“Well, fire away.”

“That’s a challenge we’ll gladly accept,” Bugsy said. “Go ahead, Jim-bo, you go first.”

“I think I will.”

It turned out, that Jim was a dentist, originally from Long Island. He ended up down South to attend dental school in Charleston, South Carolina. And that’s when he started getting into shooting — at the end of dental school and his first residency.

He got invited on his first dove shoot, borrowing a neighbors bolt-action 16 gauge. It was old and weird. “I was hooked. I had a knack for it, and killed my limit rather quickly,” Jim recalled.

Well, by now Jim is married with three children and a successful dental practice.

Jim had also turned into a dove-hunting addict; and after doves he got hooked on quail. When he couldn’t hunt birds, he started to shoot skeet. If it flied, it died, whether it sported feathers or fluorescent orange, it was going down. And as he got deeper and deeper into the shotgun sports, he joined a shooting club in Charleston, which was where he met Bugsy.

After skeet, Jim and Bugsy discovered sporting clays. They started to shoot competitively. Every weekend, Jim was out shooting – and it didn’t matter what the heck it was…doves, quail, skeet, sporting clays…

Jim was telling all of this to me, until he paused for a moment of deep reflection., where he gazed into his fate like a warrior about to face the battle of his life… “Then I got bit by the tick,” he said.

Bugsy nodded to me, puffing on his cigar.

“It’s back in ’94,” Jim said. “I was on a dove hunt in Somerville, South Carolina. I got a tick bite without even noticing it – until the rash. Things started falling apart…neurological problems…my balance gave way and I started having pains and troubles with my legs.

“For almost two years, no one could diagnose it as Lyme’s disease. I went to urologists, neurologists and internists. People weren’t aware of Lyme’s disease at this point — and they never tested him for it. Mostly I was tested for MS, and it always came back negative.

“You see, Cletus, the doctors didn’t really believe that Lyme’s disease made its way all the way down south. You know, it was first detected in Lyme Connecticut.

“In the meantime my situation is deteriorating. Well, I finally got lucky. My sister and brother-in-law are physicians, and when they finally identified the problem, they put me on antibiotics immediately. And they also hooked me up with the head of infectious disease in Columbia, in South Carolina. My sister pulled strings.”

Jim pushed out his chair. He showed me his orthopedic shoe. “That’s what Lyme’s Disease will do to you. You tell your readers, first to spray before they go out to hunt, and if they’re bitten, they should run, not walk, to get treated.”

“Jim, you gotta face it, you’ve always been jinxed,” Bugsy said. “Falling on those fire ants…that woman who got sick on the plane next to you when we flew to Argentina…”

“Well, I do live under a cloud,” Jim told me. “But I’ve never been…” He gave Bugsy a meaningful glance that only men who’ve seen it can know how meaningful it really is.

Bugsy nodded. He took a long, enjoyable puff on his cigar. “Heck, Cletus, what I’ve been through, that’s just one more good story to tell.”

And he proceeded to tell it with a flourish…

His introduction to the shotgun sports was more sordid than Jim’s. At about 14, his parents introduced him to shooting in Savannah at the Forest City Gun Club in Savannah. They took him there because it was a private club and they could drink on Sundays.

As the years passed, he never lost of his love of shooting. He started a home-building company in Columbia, South Carolina called Colony Builders.

“That was 25 years ago when I started at Colony,” he said wistfully, puffing on his cigar.

Well, in the great tradition of the South, Bugsy introduced his son, Bugsy II, to hunting. In 1998, the father took his son for his first shooting trip outside of the U.S., to Mexico, in John Wayne territory: Rio Bravo.

To minimize any dangers, Bugsy decided to stay in Texas. From their base in McAllen, Bugsy and Bugsy II would cross the Pharr Bridge and make day hunts South of the Border. Bugsy knew his outfitter well and they always adhered to the same routine. Pick-up at around noon, shoot until 6:00 or 7:00 on the preserve, and then to the world-famous La Cucaracha in Reynosa for dinner.

It was the kind of routine that men followed through the ages – for time immemorial -until such said day, when out of the blue, it happened…

“The horror,” he said, gazing into the darkness, beyond the slow river.

“Well…,” Jim said.

Bugsy, never one to lose his composure while telling a good story, sucked it up and resumed his compelling narrative.

“We were hunting some five miles from Rio Bravo when a storm came up,” he recalled. “There had been a misty rain, the kind of rain that chills men to the bones and makes you want to brew up a strong cup of Earl Grey tea.

“So we get there, three vehicles full of hunters. It clears up and the rain quits. The day before it was all dry so you could drive to the spot but now it was all gumbo and you had to walk. We walk into the field – my son and myself and the two bird boys, and we’re out in the field, it begins to rain again. I don’t mind the rain but I don’t like the lightning. You know what I mean, Cletus?”

I nodded, a somber nod, reserved for men of few words, like Clint Eastwood in The Good, The Bad and The Ugly.

But off in the distance, lightning had hit an electrical transformer – causing a loud explosion. “By my count, 1, 2, 3, I figured it was about 10 miles away,” Bugsy said.

Bugsy and Bugsy II decided to take shelter under a nearby mesquite tree. What they didn’t know, unfortunately, was that it was the devil mesquite tree.

Yes, of all the mesquite trees in all of Mexico, they unbeknownst to them stood under the mesquite tree that went by the name of El Diablo. But before any of the outfitters could warn the two men, Bugsy II had asked his father “What are the chances of getting hit by lightning here?”

Suddenly, it came up out of the ground and hit Bugsy, lifted him off the ground like El Diablo itself, and threw him down with a body slam that would’ve made Hulk Hogan proud. A fireball ran down the outside of the gun and there was a huge explosion.

“I’m going to tell you something, Cletus, that was my moment of truth. Because if that bolt of lighting had gone inside the gun, well, just let me say that I had three shells in that guy and it sure as hell would’ve gone off and killed both me and my son,” Bugsy said. “Yes, it would’ve…got us both.”

There was a silent aftermath, the kind of long silence that makes men wonder, in the solitude of the vast nothingness where men have dwelled among other men in a silence of their own, wonder to themselves as they barely move their lips “It sure is mighty quiet – too quiet.”

At first, Bugsy II thought his father had fired the gun.

Bugsy remembered what followed as clear as if he were laying in that field now.

“In my calmest voice, I said ‘I’ve been hit by lighting, I’m hurt and you need to go get help.'”

You can imagine the fortitude of this man amongst men.

From the waist down he could feel nothing whatsoever. There was a tremendous pain in his left arm, so that he actually thought it had been knocked off and sent flying clear across the field.

There was blood, plenty of it coming from somewhere and he truly believed that his arm had been knocked off and sent flying across the field, where now the vultures had gathered. And they weren’t ordinary vultures. They were the vultures known as El Diablo.

“I pulled on my arm to see if it was attached — so I realized I didn’t need a tourniquet. There was no wound either,” he described with the most masculine fortitude I’d ever heard.

As fate would have it, the wound was on his hand and it came from falling on broken glass – also known as the tears of El Diablo.

“My son runs off, through the gumbo, to get some help, and I’m on the ground, can move a thing from the waist down, and there are the bird boys, speaking Spanish to me,” Bugsy recalled. “Speaking Spanish.”

“Yes, Spanish is a very manly language,” I said.

Bugsy and Jim gave me a solemn nod.

“It took them about 40 minutes to get back though the gumbo, to find the guide on the other side of the field, and explain what happened and get them back to me,” Bugsy said. “I’d been hunting with him for about eight years and when he saw me laying there and he said, ‘Bugsy what have you done now?'”

Bugsy insisted they take him to the hospital on the other side of the border. It was the hospital known among the muscular men in this part of the world for its cherry Jell-O with fruit cocktail in it.

They got Bugsy to his feet – a brotherhood of hunters that has rung true and square through the millennium, and got him into Rio Bravo where they got a cab back to Texas. It was now about 7:00 PM, on a Saturday night, in the emergency room of a border-town hospital.

And he waited.

“By 10:00, they were bringing in the fighting victims, the knife fights, the fights of honor fought by men against men in parking lots with no name,” Bugsy said.

By time the doctors got around to Bugsy, his blood pressure was 200 over 150 (normal is about 110 over 70). The doctors gave him several doses of medicine to lower his blood pressure, sewed up his hand and kept him on a heart monitor over night.

The next morning, the doctor comes in and says to me “You were really lucky.”

“Let’s see if I understand, doc. I’m in a field with 15 guys, I get hit by lightning, and you call that lucky. I think I’d like a second opinion. The doctor said ‘that’s not what I meant’ and I said I know what you meant.”

“Yes, now I know what you mean,” I said. “Yes, yes, yes.”

Jim was puffing on his cigar through Bugsy’s tale of his travails. “Hey, Cletus, let me ask you something.”

“Sure, Jim.”

“Want to go shooting with Bugsy and me tomorrow?”

Cletus Fielding Clapp is an official correspondent for Shotgun Life. Please send your comments to letters@shotgunlife.com.

Join an elite group of readers who receive their FREE e-letter every week from Shotgun Life. These readers gain a competitive advantage from the valuable advice delivered directly to their inbox. You'll discover ways to improve your shooting, learn about the best new products and how to easily maintain your shotgun so it's always reliable. If you strive to be a better shooter, then our FREE e-letters are for you.

Shotgun Life is the first online magazine devoted to the great people who participate in the shotgun sports.

Our goal is to provide you with the best coverage in wing and clays shooting. That includes places to shoot, ways to improve your shooting and the latest new products. Everything you need to know about the shotgun sports is a mouse-click away.

Irwin Greenstein

Publisher

Shotgun Life

PO Box 6423

Thomasville, GA 31758

Phone: 229-236-1632