The Renegade Genius of the Blaser F3

Silicon Valley has popularized the term “disruptive innovation” to capture the impact of an unexpected advance in value, ingenuity and adoption on a prevailing product segment.

Disruptive innovation stems from a 1991 theory commercialized by high-tech guru, Jeffrey Moore, in his trailblazing book “Crossing the Chasm” — now seminal to Silicon Valley marketing and R&D.

In “Crossing the Chasm” Mr. Moore describes the bell-shaped adoption curve of a groundbreaking product that must leapfrog the chasm which separates a sliver of early adopters from the upsweep of mainstream acceptance. It is perhaps the most challenging gap to navigate on a product’s ascent to success.

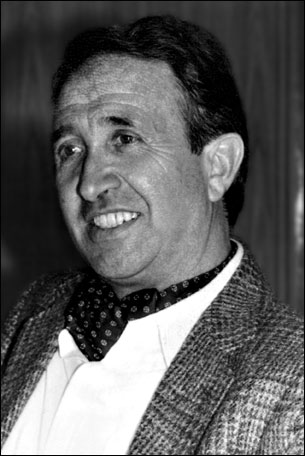

Christian Socher, CEO of Blaser USA.

Christian Socher, CEO of Blaser USA.Today, as the recent CEO of Blaser USA, Christian Socher is drawing up a strategic plan, inspired by his 10 years with the parent company in Germany where he managed international sales, that will help Blaser USA leverage its accomplishments into greater growth.

Mr. Socher relocated with his family to Blaser USA headquarters in San Antonio, Texas in 2012, taking the position of Director of Operations. Now as CEO one of his mandates is to catapult the revolutionary Blaser F3 over/under from exotic prodigy to segment frontrunner loosely defined by Perazzi, Krieghoff and Beretta.

“One thing is clear: Blaser, as a company, is very successful in Europe and now the challenge is to communicate our heritage of innovation to a larger American audience through an expanded F3 product line, compelling marketing and new dealer channels that bring the F3 closer to the larger market of recreational clays shooters,” he said.

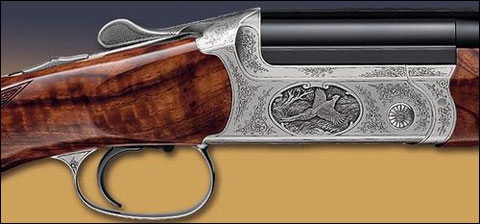

The Blaser F3 Standard model.

The Blaser F3 Standard model.When Blaser introduced Americans to the F3 in 2004, the shotgun was hailed for its low profile, unique horizontal hammers, barrel-swapping modularity, remarkable mechanical triggers and German exactitude. Although early models in the US suffered teething problems, Blaser USA rapidly rebounded though aggressive advertising that highlighted the F3’s run-up in clays tournaments as benchmarks of durability and performance.

F3 sponsored shooters included champs Bill McGuire, Joey Bolton, Janet McDougall, Cory Kruse, Diego Duarte and Mike Wilgus. As the F3 started to displace industry stalwarts on the podium, recreational weekend warriors took notice and started buying F3s. Still, sales volume never leapfrogged the marketing chasm that would take the shotgun to the next level of widespread acceptance. Now Mr. Socher believes he can do it — igniting an afterburner to American sales momentum.

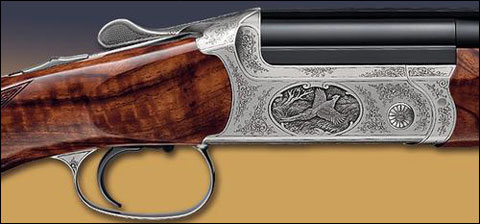

The Blaser F3 Super Luxus.

The Blaser F3 Super Luxus.The Standard F3’s starting price of about $7,000 sets down a demanding value proposition that Mr. Socher must reckon. The competition isn’t based solely on price. Given the F3’s sophistication, the market has elevated it to a category of world-class shotguns characterized by superior engineering and winning traditions in international matches.

Perazzi’s new entry-level MXS is priced within $500 of an F3 Standard Competition Sporter. The Krieghoff Parcours — the least expensive of the K-80 family — costs substantially more yet dangles the prestige of a Krieghoff for someone willing to stretch. Beretta squeezes the F3 Standard Sporter from above with its state-of-the-art DT11 ($9,000) and the 682 successor, the 692, which is the best engineered shotgun for under $5,000.

The Blaser F3 Baronesse.

The Blaser F3 Baronesse.The Blaser F3 sporting, skeet, trap and game shotguns are available in six grades starting with the Standard and escalating to the Baronesse — each upgrade featuring more intricate engraving and sumptuous walnut. Start climbing the F3 option ladder and suddenly the higher grade Krieghoffs, Perazzis and Berettas join the list of alternatives.

Looking ahead, Mr. Socher explained. “Our shotgun offers so much technical innovation that we need to communicate. Why should you shoot an F3?”

Mr. Socher’s question addresses the chasm of disruptive innovation that Blaser confronts through the F3’s unique technical architecture rendered in Isny, Germany. Company founder Horst Blaser would fully appreciate Mr. Socher’s resolution.

Company founder and engineering visionary Horst Blaser.

Company founder and engineering visionary Horst Blaser.Mr. Blaser was a car mechanic turned gunsmith formally trained to hand-make double rifles and drilling rifles. His automotive background infused the concept of precision assembly lines into a firearm trade that at the time was still largely reliant on hand-tooling.

His first production-grade rifle, called the Blaser Diplomat, was introduced in 1957. It embodied his philosophy that would define Blaser’s firearms: innovative, light-weight, precision-machined components that, ideally, were fully interchangeable.

Nearly six decades later, Blaser, recognized for extraordinary hunting rifles, introduced its first shotgun, the F3. It’s a testament to Mr. Blaser’s founding vision of modular long guns.

The Blaser R93 Attache rifle.

The Blaser R93 Attache rifle.Although Blaser started with a clean slate in devising the F3 over/under, engineers approached the project influenced by the modularity of Blaser’s R93 bolt-action rifle. The R93 receiver can quickly interchange different barrels, stocks and forends — notably maintaining uniform component weight for consistent shooting.

Blaser embraced the R93 single-receiver mandate with the F3. Most over/under target shotgun manufacturers produce two receivers: the 12 gauge plus a 20 gauge that also accommodates 28 gauge and .410 barrels. The F3 is standardized on the 12-gauge frame for monobloc 20 gauge, 28 gauge and .410 barrels. Different gauge barrels of the same length share identical weights. A 30-inch, flat-rib competition barrels about 3¼ pounds. That means Blaser clays shooters can participate in multi-gauge tournaments with full confidence their performance won’t suffer from sub-gauge, tube-set weight fluctuations.

“On the F3, our CNC machines are programmed for extremely low component tolerances, otherwise you’ll never achieve that interchangeability that was required on the rifles,” said Mr. Socher.

The barrel and stock weight balancing system of the Blaser F3 shotgun. Although the eight-pound F3 is balanced on its hinge pins, a barrel and stock weight-balancing system tailors swing and mount symmetry.

The barrel and stock weight balancing system of the Blaser F3 shotgun. Although the eight-pound F3 is balanced on its hinge pins, a barrel and stock weight-balancing system tailors swing and mount symmetry.The R93 also exercised its influence in the F3’s trigger arrangement. Dangerous-game rifle triggers demand extremely fast lock times (the milliseconds between pulling the trigger and detonation of the shell). Blaser’s solution proved ingenious in delivering dangerous-game lock times on a break-open shotgun.

The image on the left shows the horizontal firing pins of the Blaser F3 and how they synchronize with the Ejector Ball System on the right.

The image on the left shows the horizontal firing pins of the Blaser F3 and how they synchronize with the Ejector Ball System on the right.Shotgun hammers are generally cam-shaped and pivot on an axis to strike the firing pin. In effect, the hammer delivers a looping round-house punch. By comparison, the horizontal hammers in the F3 strike with an efficient short jab for faster lock times and decisive pulls at about 3¼ pounds for the mechanical trigger in an arrangement Blaser calls the Inertia Block System.

That’s because the nail-shaped F3 hammers (also called strikers or plungers) are driven horizontally by coil springs embedded in channels machined into the receiver. The linear travel enables both a quicker, center-line strike (ignition) and lower profile compared with more conventional over/under actions.

The integrated Ejector Ball System also contributed to the low profile with a very elegant design.

Typical ejectors cock the springs upon closing the shotgun. The EBS actuates the ejectors when the shot is fired and the gun opened — minimizing resistance when closing the gun for the next shot.

Clearly the F3 is an iconoclast — a technological disrupter.

Blaser’s F3 SuperTrap Combo with single and over/barrel barrels.

Blaser’s F3 SuperTrap Combo with single and over/barrel barrels.Now Mr. Socher must convey the magic of the F3 to a larger audience of wing and clays shooters. He’s relying on his team of Andre Gorjup who heads up Service; shooting instructor and referee Mo Parsons as Product Manager Shotguns; and Janet McDougall, an F3 competitive shooter and Blaser veteran, as CFO.

First order of business is new models. Blaser has recently introduced skeet and game versions of the F3. We may see a new mid-range F3 this year slotted between the Standard and the higher grade Luxus. And Mr. Socher referred to the possibility of a woman’s F3 with dimensions compatible for greater comfort.

Janet McDougall is CFO of Blaser USA and a Blaser competitive shooter.

Janet McDougall is CFO of Blaser USA and a Blaser competitive shooter.The Standard F3 tends to polarize shooters with its plain satin finish. In response, Mr. Socher said “We will push the cosmetic side.”

He expects more emphasis on service with Mr. Gorjup taking the lead in San Antonio.

So far, Blaser has focused on competitive shooters, but Mr. Socher sees huge potential in the recreational shooter market, or as he described them “People who like to shoot and can afford a nice, high-end shotgun.” One option is to place the F3 in shooting clubs and resorts.

“We want to create a buffer around the company as one that is seen as forward thinking and innovative — to get this Blaser feeling of engineering into US,” he explained. “When an F3 is sitting on a gun rack with other shotguns, we want people to think of the F3 owner as a smart guy.”

Irwin Greenstein is the Publisher of Shotgun Life. You can reach him at contact@shotgunlife.com.

Useful resources:

The Blaser USA web site

Irwin Greenstein is Publisher of Shotgun Life. Please send your comments to letters@shotgunlife.com.

Comments